Part of Series

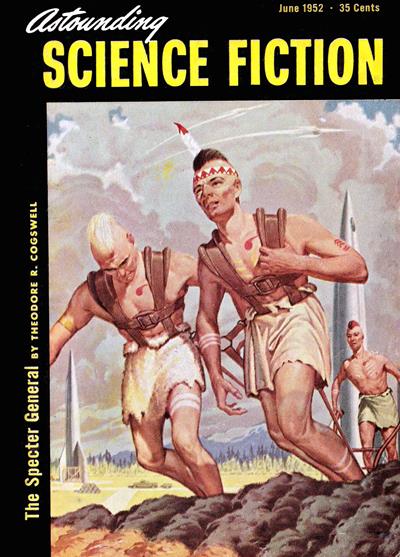

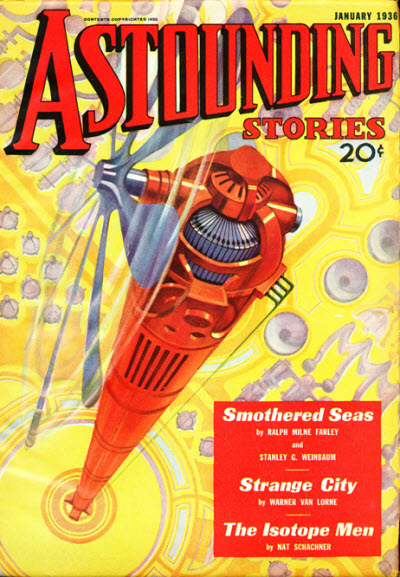

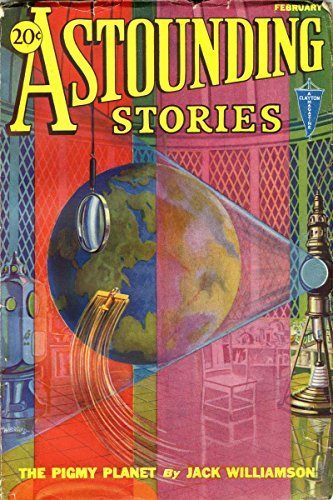

Vol 9, No 2 Contents: 151 • The Pygmy Planet • novelette by Jack Williamson 168 • Wandl, the Invader (Part 1 of 4) • [Gregg Haljan • 2] • serial by Ray Cummings 202 • Seed of the Arctic Ice • [Seed of the Arctic Ice • 1] • short story by Harry Bates and D. W. Hall [as by H. G. Winter] 222 • The Space Rover • novelette by Edwin K. Sloat 238 • The Mind Master (Part 2 of 2) • [Caleb Barter • 2] • serial by Arthur J. Burks 264 • Zehru of Xollar • short story by Hal K. Wells 279 • The Readers' Corner (Astounding Stories, February 1932) • [The Readers' Corner] • essay by The Editor Inspired by the success of Hugo Gernsback's Amazing Stories, Clayton Publishing Co. released, in January of 1930, the first issue of Astounding Stories. Early issues lacked much of Gernsback's attention to the scientific and extrapolative possibilities of the SF genre, and instead featured many instances of stock, pulp adventure yarns simply transplanted into exotic or alien environments. While possibly a travesty in the eyes of SF purists, it attracted many SF fans and general pulp readers, and aided Astounding's first three years of survival, until its cancellation during the height of the Great Depression in March of 1933. Thankfully, the departure was short-lived; the pulp industry giant Street & Smith Corp. purchased the title, and in October 1933 Astounding Stories returned. The stock adventure stories that had appeared previously were replaced, with what editor F. Orlin Tremaine dubbed "thought-variants:" stories that were just as interesting and exciting, but also held some scientific or technological truth at their core. This approach—combining the adventure of the pulps with the ideas of Gernsbackian extrapolation—in addition to the social, political and introspective elements increasingly incorporated by its authors' stories, would help define Astounding in the coming years. In other words, it was no longer an Amazing Stories clone, or an adventure magazine masquerading as SF, but a unique addition to the growing stable of SF literature. In May of 1938, John Wood Campbell, a writer and assistant editor under Tremaine, took over the editorship of Astounding Stories; Cambell would hold this post for thirty-three years—a remarkable tenure in itself—during which time he helped shape science fiction literature for many more decades to come. It was in this period that Campbell discovered such SF mainstays as Lester del Rey, Theodore Sturgeon, Clifford Simak, Isaac Asimov, and L. Ron Hubbard. Hubbard's dianetic theories were introduced to readers of the magazine in May 1950. Honoring Tremaine’s "thought-variants," Campbell wanted stories that were "from the view of a man involved in the events . . . rather than . . . a story of a gadget," as Lester del Rey described Campbell's approach. One was more likely to find a rookie starship crewman or hitherto unrecognized scientific prodigy as the protagonist of a Campbell story, as opposed to the ace space captain or world-renowned physicist that had made up the bulk of SF heroes dating back to the days of Gernsback. As Campbell wrote in an editorial, "It is the man, not the idea or machine that is the essence [of SF]." Continuing an Astounding tradition that had dated back to its inception, Campbell paid top dollar, on time, to his authors (something Gernsback and many other SF magazine editors rarely succeeded in doing). This practice guaranteed that not only seasoned SF veterans but also budding hopefuls often submitted their manuscripts to Campbell's editorial offices first. Along with Amazing Stories' "Discussions," Astounding's letters section, "Brass Tacks," also served as an important venue for communication and discussion within the emerging, organized SF fan community. Hoping to distance the magazine further from its more sensationalized pulp origins—and subsequently to create a more "futurology"-oriented image for it—Campbell changed the magazine's title to Astounding Science Fiction in 1938, and later to Analog Science Fact & Fiction in 1960. In November 1992, the logo was revised to read "Fiction and Fact" rather than "Fact & Fiction," but Analog is the name by which the magazine is still known to this day. 【 PREVIOUS ISSUE ← February 1932 → NEXT ISSUE 】

Author

No contributors found for this work.