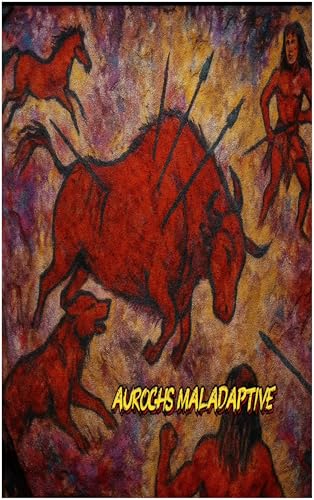

International Gold Winner of the Readers’ Choice Book Awards (What Light Was), novelist Shawn Callaway Hays delivers Aurochs Maladaptive. In Aurochs Maladaptive, poet-philosopher Shawn Callaway Hays constructs a mythopoetic archive of pain, memory, and perseverance. This deeply ambitious and lyrically sculpted collection of 35 poems revives one of the most ancient figures etched into Western the aurochs, the great horned oxen of Paleolithic Europe, painted across the walls of Lascaux and hunted to extinction by the relentless apparatus of civilization. But these aurochs are no mere historical symbols—they are animated here as tragic avatars of human maladaptive, misunderstood, and magnificently unyielding. Structured as a compressed lyric cycle in formal dialogue with Théophile Gautier’s Enamels and Cameos (itself a landmark of precision and ornamental beauty), Aurochs Maladaptive positions itself at the intersection of epic, elegy, and confessional. Through a voice that fuses the moral gravity of Milton with the democratic breath of Whitman, Hays’s aurochs-poets speak from the interior of extinction. They articulate a liminal condition in which myth, masculinity, trauma, and theological fracture coalesce. Their maladaptation becomes a resistance to erasure—a refusal to evolve away from empathy, memory, and mythic burden. These poems draw from a broad tapestry of historical, biblical, and philosophical sources. References collide with primal a pelican bleeding for its young, a ballet of wrathful swan-women, a child in a post-9/11 classroom learning to grieve. The result is a poetics of montage and lament, wherein each image is a fresco—precise, archaic, and affectively raw. Central to the collection is a metaphysical meditation on forbearance, and fierce individuality. Hays’s narrators—orphans, prophets, wounded sons, misfit saints—are trapped within structures they neither created nor can easily Western inheritance, religious ruin, masculine silence, historical violence. But rather than collapse into nihilism, the poems confront annihilation with lyric fire. They do not plead for rescue—they become the means of their own salvage, lit by the sparks of vision and utterance. Standout works such as “his name was Ishmael and he lost” and “annihilation eclipsed” anchor the collection with prophetic force. In the former, Hays stages a metaphysical shipwreck, placing the postmodern orphan into dialogue with Melville’s Ishmael, the castaway, and the wreckage of American empire. In the latter, the fleeting hush of an eclipse becomes a figure for grace deferred—where cosmic alignment gestures toward hope, but does not guarantee it. These are not romantic gestures toward transcendence; they are fierce articulations of the human as radically endangered, yet untamed. Throughout the collection, Hays constructs what might be called a salvific poetics of maladaptation. The aurochs are maladaptive precisely because they refuse to comply with the brutal efficiencies of modern progress. Their sacred futility becomes a theological and poetic stance—a refusal to be controlled, extinguished, or made useful. Hays’s use of extinction as a metaphor is not sentimental but sacramental. Ultimately, Aurochs Maladaptive offers a poetic gospel for the wounded and defiant—a text that insists survival is not synonymous with submission. Rather, it posits art as the sacred maladaptive the refusal to forget, the refusal to evolve beyond love, the refusal to stop naming what has been lost.