Books in series

Commentary on the Gospel of St. Matthew

1841

Catena Aurea

Commentary on the Four Gospels, Collected Out of the Works of the Fathers, Volume IV Part 2, Gospel of St. John

1980

Author

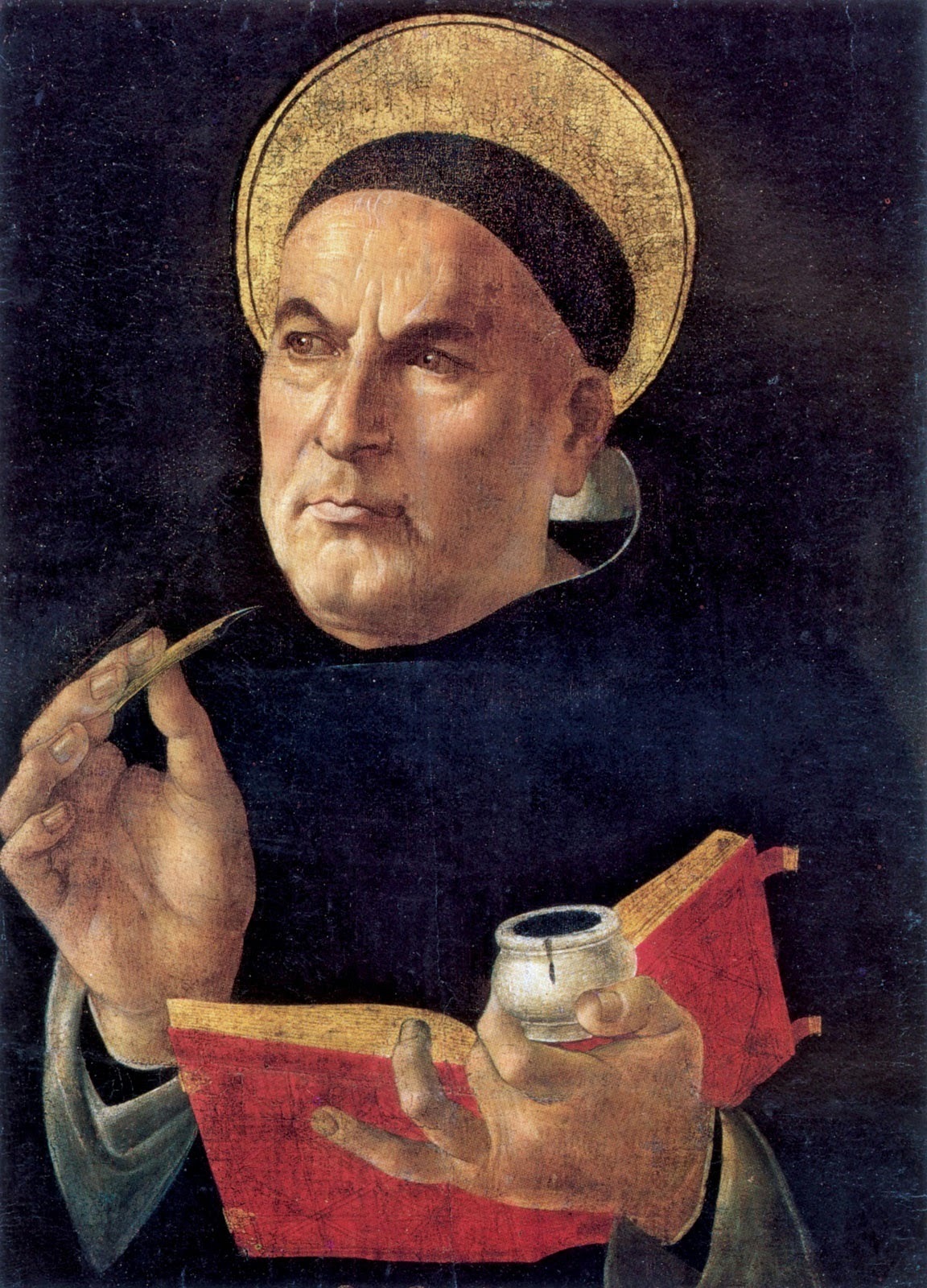

Philosophy of Saint Thomas Aquinas, a Dominican friar and theologian of Italy and the most influential thinker of the medieval period, combined doctrine of Aristotle and elements of Neoplatonism, a system that Plotinus and his successors developed and based on that of Plato, within a context of Christian thought; his works include the Summa contra gentiles (1259-1264) and the Summa theologiae or theologica (1266-1273). Saint Albertus Magnus taught Saint Thomas Aquinas. People ably note this priest, sometimes styled of Aquin or Aquino, as a scholastic. The Roman Catholic tradition honors him as a "doctor of the Church." Aquinas lived at a critical juncture of western culture when the arrival of the Aristotelian corpus in Latin translation reopened the question of the relation between faith and reason, calling into question the modus vivendi that obtained for centuries. This crisis flared just as people founded universities. Thomas after early studies at Montecassino moved to the University of Naples, where he met members of the new Dominican order. At Naples too, Thomas first extended contact with the new learning. He joined the Dominican order and then went north to study with Albertus Magnus, author of a paraphrase of the Aristotelian corpus. Thomas completed his studies at the University of Paris, formed out the monastic schools on the left bank and the cathedral school at Notre Dame. In two stints as a regent master, Thomas defended the mendicant orders and of greater historical importance countered both the interpretations of Averroës of Aristotle and the Franciscan tendency to reject Greek philosophy. The result, a new modus vivendi between faith and philosophy, survived until the rise of the new physics. The Catholic Church over the centuries regularly and consistently reaffirmed the central importance of work of Thomas for understanding its teachings concerning the Christian revelation, and his close textual commentaries on Aristotle represent a cultural resource, now receiving increased recognition.