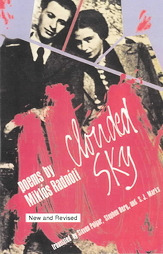

"...a truly great poet, one in whom the lyrical image-maker and the critical human intelligence dealing with the tragic twentieth century are utterly fused, as they so rarely are . . . The quality of the translation is such that it is hard to remember the poems were not first written in English, even though one is always aware of Radnoti's vision as European and of his locus as Hungary."—Denise Levertov The Hungarian Jewish poet Miklos Radnoti (1909-1944) was also a prolific translator and editor who wrote some of his greatest poems in the labor camps and copper mines of Yugoslavia before being killed by the Nazis. Leaving behind a body of work that ranks with the classics of Hungarian verse, his influence is now being felt among a younger generation. In 1946, Radnoti's body was exhumed from a mass grave by his wife who found a notebook of his poems (many of which were addressed to her) in his coat pocket.

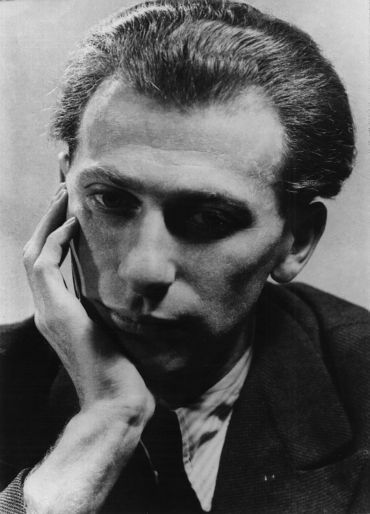

Author

Miklós Radnóti, birth name Miklós Glatter, was a Hungarian poet who fell victim to the Holocaust. Radnóti was born into an assimilated Jewish family. His life was considerably shaped by the fact that both his mother and his twin brother died at his birth. He refers to this trauma in the title of his compilation Ikrek hava ("Month of Gemini"/"Month of the Twins"). Though in his last years, Hungarian society rejected him as a Jew, in his poems he identifies himself very strongly as a Hungarian. His poetry mingles avant-garde and expressionist themes with a new classical style, a good example being his eclogues. His romantic love poetry is notable as well. Some of his early poetry was published in the short-lived periodical Haladás (Progress). His 1935 marriage to Fanni Gyarmati (born 1912) was exceptionally happy. Radnóti converted to Catholicism in 1943. This was partly prompted by the persecution of the Hungarian Jews (from which converts to Christianity were initially exempted), but partly also with his long-standing fascination with Catholicism. In the early forties, he was conscripted by the Hungarian Army, but being a Jew, he was assigned to an unarmed support battalion (munkaszolgálat) in the Ukrainian front. In May 1944, the defeated Hungarians retreated and Radnóti's labor battalion was assigned to the Bor, Serbia copper mines. In August 1944, as consequence of Tito's advance, Radnóti's group of 3,200 Hungarian Jews was force-marched to Central Hungary, which very few reached alive. Radnóti was fated not to be among them. Throughout these last months of his life, he continued to write poems in a little notebook he kept with him. According to witnesses, in early November 1944, Radnóti was severely beaten by a drunken militiaman, who had been tormenting him for "scribbling". Too weak to continue, he was shot into a mass grave near the village of Abda in Northwestern Hungary. Today, a statue next to the road commemorates his death on this spot. Eighteen months later, his body was unearthed and in the front pocket of his overcoat the small notebook of his final poems was discovered (his body was later reinterred in Budapest's Kerepesi Cemetery). These final poems are lyrical and poignant and represent some of the few works of literature composed during the Holocaust that survived. Possibly his best known poem is the fourth stanza of the Razglednicák, where he describes the shooting of another man and then envisions his own death.