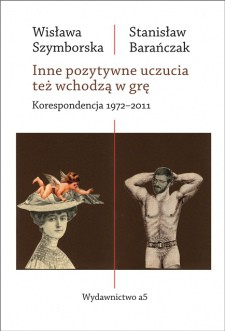

Odczytane z rękopisów listy, po raz pierwszy publikowane wyklejanki i drobiazgowe przypisy Ryszarda Krynickiego składają się na fascynujący, bogaty i wielowymiarowy portret literackiej przyjaźni Wisławy Szymborskiej i Stanisława Barańczaka. Książka jest efektem pracy w archiwum Wisławy Szymborskiej zdeponowanym w Bibliotece Jagiellońskiej, gdzie znajduje się około 80 listów Stanisława Barańczaka do Wisławy Szymborskiej. Korespondencja zawiera też karty pocztowe oraz różnego typu załączniki, głównie dołączane do listów teksty literackie. Ta część korespondencji została umieszczona przez Wisławę Szymborską w teczce opisanej „Barańczak. Jego cudeńka”, zawierającej również listy do Michała Rusinka i kopie przekładów Stanisława Barańczaka wierszy żartobliwych i dziwacznych oraz zabaw słownych z dedykacjami dla Noblistki. Listy Wisławy Szymborskiej są przechowywane w archiwum domowym Stanisława Barańczaka w Newtonville pod Bostonem; wśród listów znajdują się nieznane dotąd wyklejanki. Inne pozytywne uczucia… to portret literackiej przyjaźni, najpierw wynikającej z wzajemnego zainteresowania swoją twórczością, z czasem coraz częściej do głosu dochodzi sfera prywatna, którą oboje zwykli starannie chronić. Około połowy lat 70. Barańczak powściągliwie nawiązuje do swej niełatwej sytuacji po utracie pracy, a po wyjeździe do Stanów – do doświadczeń emigranckich, wreszcie w latach 90. - do pogarszającego się zdrowia. Korespondencja jest również świadectwem amerykańskiej percepcji poezji Wisławy Szymborskiej i Jej wstępowania w krąg najwyżej cenionych za oceanem poetów. Równie istotny jest wpisany w te listy zapis samoświadomości Barańczaka jako tłumacza i interpretatora poezji. Formatem i szatą graficzną tom nawiązuje do wydanej przez Wydawnictwo a5 w 2018 roku korespondencji Wisławy Szymborskiej i Zbigniewa Herberta pt. Jacyś złośliwi bogowie zakpili z nas okrutnie. Korespondencja 1955-1996. Bogato ilustrowany faksymilami i reprodukcjami wyklejanek, uzupełniony obszernymi przypisami Ryszarda Krynickiego.

Authors

Wisława Szymborska (Polish pronunciation: [vʲisˈwava ʂɨmˈbɔrska], born July 2, 1923 in Kórnik, Poland) is a Polish poet, essayist, and translator. She was awarded the 1996 Nobel Prize in Literature. In Poland, her books reach sales rivaling prominent prose authors—although she once remarked in a poem entitled "Some like poetry" [Niektórzy lubią poezję] that no more than two out of a thousand people care for the art. Szymborska frequently employs literary devices such as irony, paradox, contradiction, and understatement, to illuminate philosophical themes and obsessions. Szymborska's compact poems often conjure large existential puzzles, touching on issues of ethical import, and reflecting on the condition of people both as individuals and as members of human society. Szymborska's style is succinct and marked by introspection and wit. Szymborska's reputation rests on a relatively small body of work: she has not published more than 250 poems to date. She is often described as modest to the point of shyness[citation needed]. She has long been cherished by Polish literary contemporaries (including Czesław Miłosz) and her poetry has been set to music by Zbigniew Preisner. Szymborska became better known internationally after she was awarded the 1996 Nobel Prize. Szymborska's work has been translated into many European languages, as well as into Arabic, Hebrew, Japanese and Chinese. In 1931, Szymborska's family moved to Kraków. She has been linked with this city, where she studied, worked. When World War II broke out in 1939, she continued her education in underground lessons. From 1943, she worked as a railroad employee and managed to avoid being deported to Germany as a forced labourer. It was during this time that her career as an artist began with illustrations for an English-language textbook. She also began writing stories and occasional poems. Beginning in 1945, Szymborska took up studies of Polish language and literature before switching to sociology at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków. There she soon became involved in the local writing scene, and met and was influenced by Czesław Miłosz. In March 1945, she published her first poem Szukam słowa ("I seek the word") in the daily paper Dziennik Polski; her poems continued to be published in various newspapers and periodicals for a number of years. In 1948 she quit her studies without a degree, due to her poor financial circumstances; the same year, she married poet Adam Włodek, whom she divorced in 1954. At that time, she was working as a secretary for an educational biweekly magazine as well as an illustrator. During Stalinism in Poland in 1953 she participated in the defamation of Catholic priests from Kraków who were groundlessly condemned by the ruling Communists to death.[1] Her first book was to be published in 1949, but did not pass censorship as it "did not meet socialist requirements." Like many other intellectuals in post-war Poland, however, Szymborska remained loyal to the PRL official ideology early in her career, signing political petitions and praising Stalin, Lenin and the realities of socialism. This attitude is seen in her debut collection Dlatego żyjemy ("That is what we are living for"), containing the poems Lenin and Młodzieży budującej Nową Hutę ("For the Youth that Builds Nowa Huta"), about the construction of a Stalinist industrial town near Kraków. She also became a member of the ruling Polish United Workers' Party. Like many Polish intellectuals initially close to the official party line, Szymborska gradually grew estranged from socialist ideology and renounced her earlier political work. Although she did not officially leave the party until 1966, she began to establish contacts with dissidents. As early as 1957, she befriended Jerzy Giedroyc, the editor of the influential Paris-based emigré journal Kultura, to which she also contributed. In 1964 s