CHAPTER III. A MYSTERIOUS TOMB One member of the Braddock household was not included in the general staff, being a mere appendage of the Professor himself. This was a dwarfish, misshapen Kanaka, a pigmy in height, but a giant in breadth, with short, thick legs, and long, powerful arms. He had a large head, and a somewhat handsome face, with melancholy black eyes and a fine set of white teeth. Like most Polynesians, his skin was of a pale bronze and elaborately tattooed, even the cheeks and chin being scored with curves and straight lines of mystical import. But the most noticeable thing about him was his huge mop of frizzled hair, which, by some process, known only to himself, he usually dyed a vivid yellow. The flaring locks streaming from his head made him resemble a Peruvian image of the sun, and it was this peculiar coiffure which had procured for him the odd name of Cockatoo. The fact that this grotesque creature invariably wore a white drill suit, emphasized still more the suggestion of his likeness to an Australian parrot. Cockatoo had come from the Solomon Islands in his teens to the colony of Queensland, to work on the plantations, and there the Professor had picked him up as his body servant. When Braddock returned to marry Mrs. Kendal, the boy had refused to leave him, although it was represented to the young savage that he was somewhat too barbaric for sober England. Finally, the Professor had consented to bring him over seas, and had never regretted doing so, for Cockatoo, finding his scientific master a true friend, worshipped him as a visible god. Having been captured when young by Pacific black-birders, he talked excellent English, and from contact with the necessary restraints of civilization was, on the whole, extremely well behaved. Occasionally, when teased by the villagers and his fellow-servants, he would break into childish rages, which bordered on the dangerous. But a word from Braddock always quieted him, and when penitent he would crawl like a whipped dog to the feet of his divinity. For the most part he lived entirely in the museum, looking after the collection and guarding it from harm. Lucy - who had a horror of the creature's uncanny looks - objected to Cockatoo waiting at the table, and it was only on rare occasions that he was permitted to assist the harassed parlormaid. On this night the Kanaka acted excellently as a butler, and crept softly round the table, attending to the needs of the diners. He was an admirable servant, deft and handy, but his blue-lined face and squat figure together with the obtrusively golden halo, rather worried Mrs. Jasher. And, indeed, in spite of custom, Lucy also felt uncomfortable when this gnome hovered at her elbow. It looked as though one of the fantastical idols from the museum below had come to haunt the living.

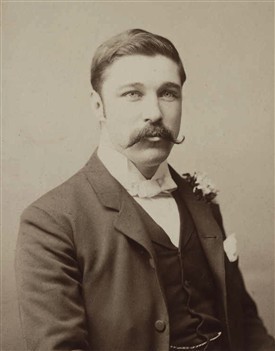

Author

Fergusson Wright Hume (1859–1932), New Zealand lawyer and prolific author particularly renowned for his debut novel, the international best-seller The Mystery of a Hansom Cab (1886). Hume was born at Powick, Worcestershire, England, son of Glaswegian Dr. James Collin Hume, a steward at the Worcestershire Pauper Lunatic Asylum and his wife Mary Ferguson. While Fergus was a very young child, in 1863 the Humes emigrated to New Zealand where James founded the first private mental hospital and Dunedin College. Young Fergus attended the Otago Boys' High School then went on to study law at Otago University. He followed up with articling in the attorney-general's office, called to the New Zealand bar in 1885. In 1885 Hume moved to Melbourne. While he worked as a solicitors clerk he was bent on becoming a dramatist; but having only written a few short stories he was a virtual unknown. So as to gain the attentions of the theatre directors he asked a local bookseller what style of book he sold most. Emile Gaboriau's detective works were very popular and so Hume bought them all and studied them intently, thus turning his pen to writing his own style of crime novel and mystery. Hume spent much time in Little Bourke Street to gather material and his first effort was The Mystery of a Hansom Cab (1886), a worthy contibution to the genre. It is full of literary references and quotations; finely crafted complex characters and their sometimes ambiguous seeming interrelationships with the other suspects, deepening the whodunit angle. It is somewhat of an exposé of the then extremes in Melbourne society, which caused some controversy for a time. Hume had it published privately after it had been downright rudely rejected by a number of publishers. "Having completed the book, I tried to get it published, but everyone to whom I offered it refused even to look at the manuscript on the grounds that no Colonial could write anything worth reading." He had sold the publishing rights for £50, but still retained the dramatic rights which he soon profited from by the long Australian and London theatre runs. Except for short trips to France, Switzerland and Italy, in 1888 Hume settled and stayed in Essex, England where he would remain for the rest of his life. Although he was born and lived the latter part of this life in England, he thought of himself as 'a colonial' and identified as a New Zealander, having spent all of his formative years from preschool through to adulthood there. Hume died of cardiac failure at his home on 11 July 1932.