“When this book was first published it received some attention from the critics but none at all from the public. Nazism was finished in the bunker in Berlin and its death warrant signed on the bench at Nuremberg.” That’s Milton Mayer, writing in a foreword to the 1966 edition of They Thought They Were Free. He’s right about the critics: the book was a finalist for the National Book Award in 1956. General readers may have been slower to take notice, but over time they did—what we’ve seen over decades is that any time people, across the political spectrum, start to feel that freedom is threatened, the book experiences a ripple of word-of-mouth interest. And that interest has never been more prominent or potent than what we’ve seen in the past year. They Thought They Were Free is an eloquent and provocative examination of the development of fascism in Germany. Mayer’s book is a study of ten Germans and their lives from 1933-45, based on interviews he conducted after the war when he lived in Germany. Mayer had a position as a research professor at the University of Frankfurt and lived in a nearby small Hessian town which he disguised with the name “Kronenberg.” “These ten men were not men of distinction,” Mayer noted, but they had been members of the Nazi Party; Mayer wanted to discover what had made them Nazis. His discussions with them of Nazism, the rise of the Reich, and mass complicity with evil became the backbone of this book, an indictment of the ordinary German that is all the more powerful for its refusal to let the rest of us pretend that our moment, our society, our country are fundamentally immune. A new foreword to this edition by eminent historian of the Reich Richard J. Evans puts the book in historical and contemporary context. We live in an age of fervid politics and hyperbolic rhetoric. They Thought They Were Free cuts through that, revealing instead the slow, quiet accretions of change, complicity, and abdication of moral authority that quietly mark the rise of evil.

Author

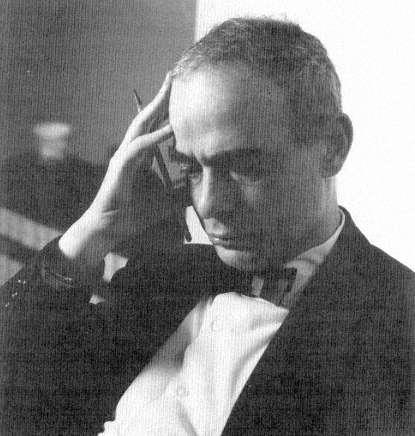

Milton Sanford Mayer, a journalist and educator, was best known for his long-running column in The Progressive magazine, founded by Robert Marion LaFollette, Sr in Madison, Wisconsin. Mayer, raised a Reform Jew, was born in Chicago, the son of Morris Samuel Mayer and Louise (Gerson). He graduated from Englewood High School, where he received a classical education with an emphasis on Latin and languages. He studied at the University of Chicago from 1925 to 1928 but did not earn a degree; he told the Saturday Evening Post in 1942 that he was "placed on permanent probation in 1928 for throwing beer bottles out a dormitory window." He was a reporter for the Associated Press (1928-29), the Chicago Evening Post, and the Chicago Evening American. During his stint at the Post he married his first wife Bertha Tepper (the couple had two daughters). In 1945 they were divorced, and two years later Mayer married Jane Scully, whom he referred to as "Baby" in his magazine columns. At various times, he taught at the University of Chicago, the University of Massachusetts, and the University of Louisville, as well as universities abroad. He was also a consultant to the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions. Mayer's most influential book was probably They Thought They Were Free: The Germans, 1933-45, a study of the lives of a group of ordinary Germans under the Third Reich, first published in 1955 by the University of Chicago Press. (Mayer became a member of the Religious Society of Friends or Quakers while he was researching this book in Germany in 1950; he did not reject his Jewish birth and heritage.) At various times, he taught at the University of Chicago, the University of Massachusetts, and the University of Louisville, as well as universities abroad. He was also a consultant to the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions. Mayer is also the author of What Can a Man Do? (Univ. of Chicago Press) and is the co-author, with Mortimer Adler, of The Revolution in Education (Univ. of Chicago Press). Mayer died in 1986 in Carmel, California, where he and his second wife made their home. Milton had one brother, Howie Mayer, who was the Chicago journalist that broke the Leopold and Loeb case.