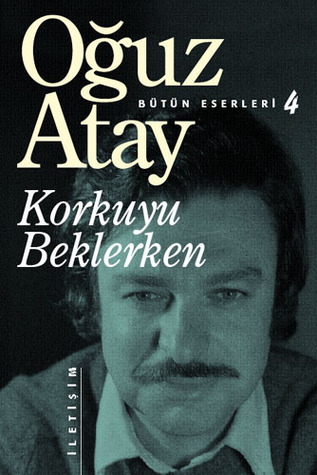

Oğuz Atay (1934-1977), one of the most influential figures of 20th-century Turkish literature, was not only a writer and a professor, but also a civil engineer. Aside from his widely acclaimed novels, in this book of collected stories, Atay engineers the language of a historically multilayered society that was in the midst of a cultural and political transition. By smoothly mending the autobiographical and the fictional, he invites the reader into a maze of seamlessly shifting narrative voices. Atay cracks the walls constructed over time between singular and plural pronouns, between the rather ambiguous victims and victors of each story. Without merely trying to impose pity for the 'other, ' he traces the existential conflicts of different 'selves' struggling to survive and peels away the layers of each isolated and alienated persona while standing at an equally critical distance to the social stratifications each layer signifies. Atay's lingual precision in short-circuiting familiar processes of reasoning and memory within the daily flow of time, along with his dark, yet highly ironic tone in dismantling the edifices of social norms call to mind writers such as Dostoevsky, Kafka, and Joyce. This is the first translation of Waiting for Fear into English.

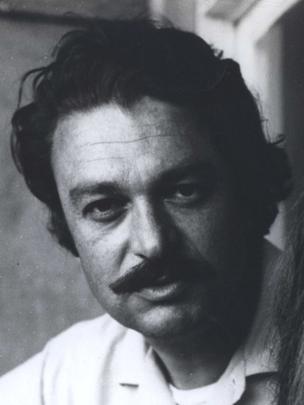

Author

Oğuz Atay (1934–1977) was a pioneer of the modern novel in Turkey. His first novel, Tutunamayanlar (The Disconnected), appeared 1971-72. Never reprinted in his lifetime and controversial among critics, it has become a best-seller since a new edition came out in 1984. It has been described as “probably the most eminent novel of twentieth-century Turkish literature”: this reference is due to a UNESCO survey, which goes on: “it poses an earnest challenge to even the most skilled translator with its kaleidoscope of colloquialisms and sheer size.” In fact one translation has so far been published, into Dutch: Het leven in stukken, translated by Hanneke van der Heijden and Margreet Dorleijn (Athenaeum-Polak & v Gennep, 2011). It appears also that a complete English translation exists, of which an excerpt won the Dryden Translation Prize in 2008: Comparative Critical Studies, vol.V (2008) 99. His book of short stories, Korkuyu Beklerken, has appeared in a French translation by Jocelyne Burkmann and Ali Terzioglu as En guettant la peur, Paris, L'Harmattan, March 2010. He was born October 12, 1934 in İnebolu, a small town (population less than 10,000) in the centre of the Black Sea coast, 590 km from İstanbul. His father was a judge and his mother a schoolteacher, thus both representative of the modernization of Turkey brought about by Atatürk. Although he lived most of his life in big cities this provincial background was important to his work. He was at high school in Ankara, at Ankara College until 1951, and after military service enrolled at Istanbul Technical University, where he graduated as a civil engineer in 1957. With a friend he started an enterprise as a building contractor. This failed, leaving him (as such experiences have for other novelists) valuable material for his writing. In 1960 he joined the staff of the İstanbul Academy of Engineering and Architecture, where he worked until his final illness; he was promoted to associate professorship in 1970, for which he presented as his qualification a textbook on surveying, Topoğrafya. His first creative work, Tutunamayanlar, was awarded the prize of Turkish Radio Television Institution, TRT in 1970, before it had been published. He went on to write another novel and a volume of short stories among other works. He died in İstanbul, December 13, 1977, of a brain tumour. He spent much of his last year in London, where he had gone for treatment. He is buried in Edirnekapı Martyr's Cemetery. He married twice, and is survived by a daughter, Özge, by his first marriage. Atay was of a generation deeply committed to the Westernising, scientific, secular culture encouraged by the revolution of the 1920s; he had no nostalgia for the corruption of the late Ottoman Empire, though he knew its literature, and was in particular well versed in Divan poetry. Yet the Western culture he saw around him was largely a form of colonialism, tending to crush what he saw was best about Turkish life. He had no patience with the traditionalists, who countered Western culture with improbable stories of early Turkish history. He soon lost patience with the underground socialists of the 1960s. And, although some good writers, such as Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar, had written fiction dealing with the modernisation of Turkey, there were none that came near to dealing with life as he saw it lived. In fact, almost the only Turkish writer of the Republican period whose name appears in his work is the poet Nâzim Hikmet. The solution lay in using the West for his own ends. His subject matter is frequently the detritus of Western culture—translations of tenth-rate historical novels, Hollywood fantasy films, trivialities of encyclopaedias, Turkish tangos.... — but it is plain to any reader that he had a deep knowledge of Western literature. First come the great Russians, particularly Dostoevsky, with a particular liking for Ivan Goncharov's Oblomov: he was not alone in seeing a peculiar affinity betwee