Books in series

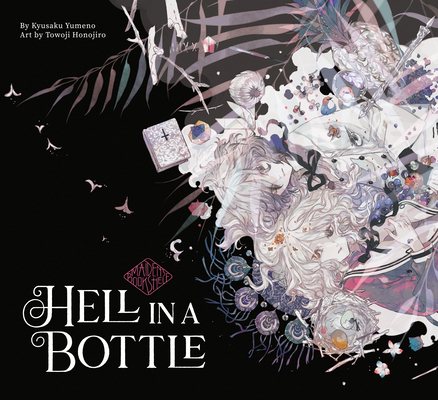

Hell in a Bottle

Maiden's Bookshelf

1928

![猫町 [Nekomachi] book cover](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1677798402i/6226750.jpg)

猫町 [Nekomachi]

1997

The Moon Over the Mountain

Maiden's Bookshelf

1942

女生徒

1939

The Surgery Room

Maiden's Bookshelf

1895

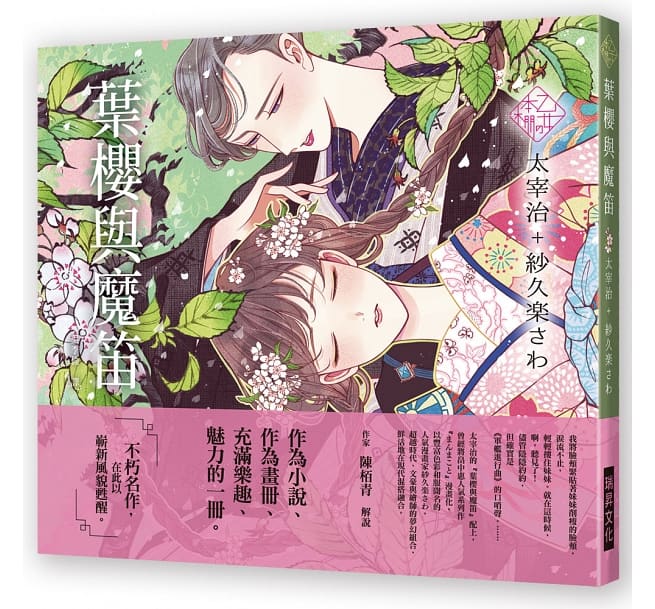

葉櫻與魔笛

2016

The Girl Who Became a Fish

Maiden's Bookshelf

1933

Spring Comes Riding in a Carriage

Maiden's Bookshelf

2021

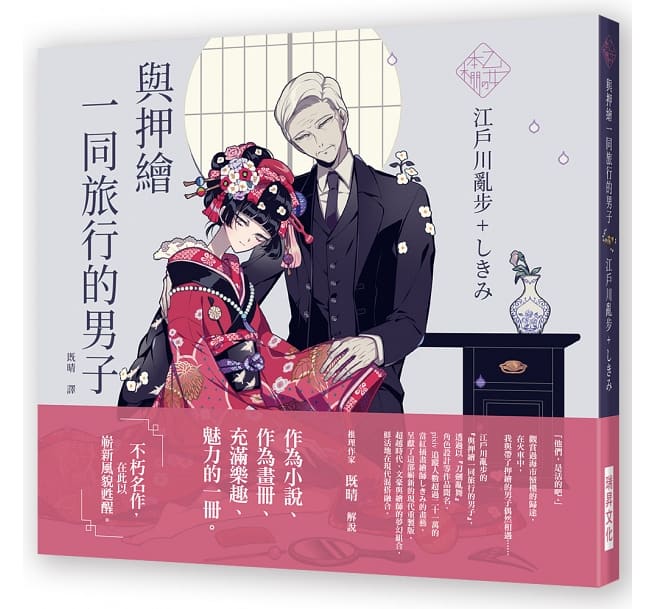

與押繪一同旅行的男子

2019

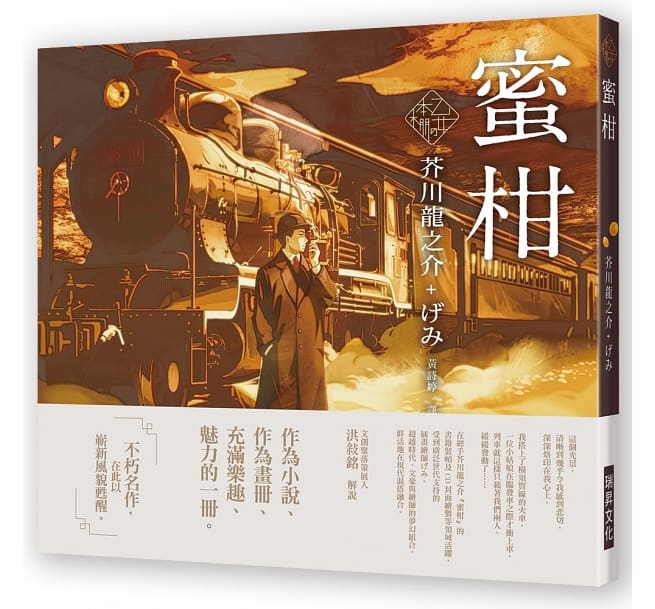

蜜柑

2018

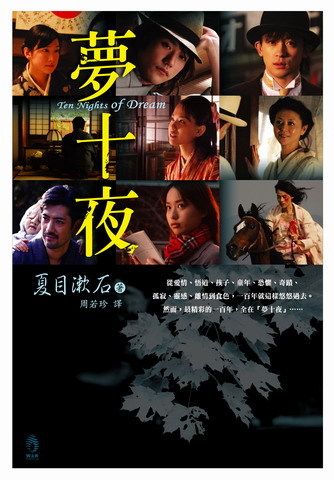

夢十夜

2013

赤とんぼ

2019

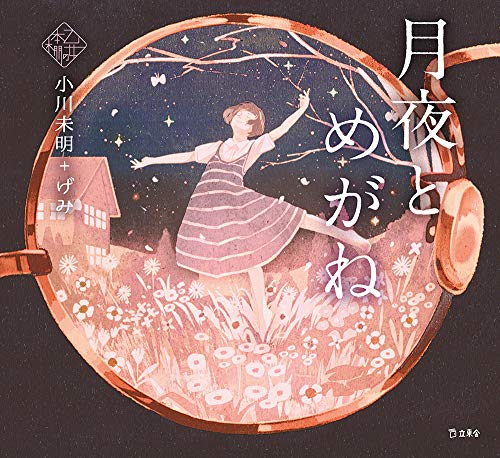

月夜とめがね

2023

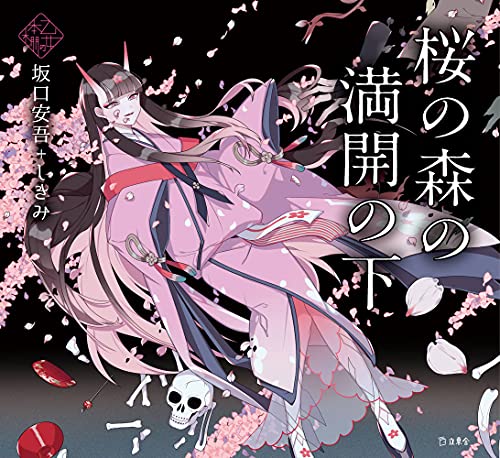

桜の森の満開の下

2019

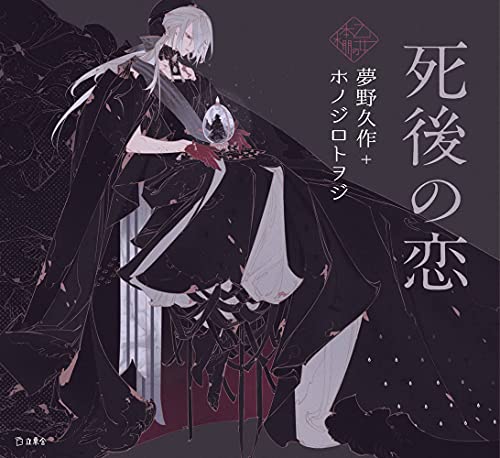

死後の恋

2025

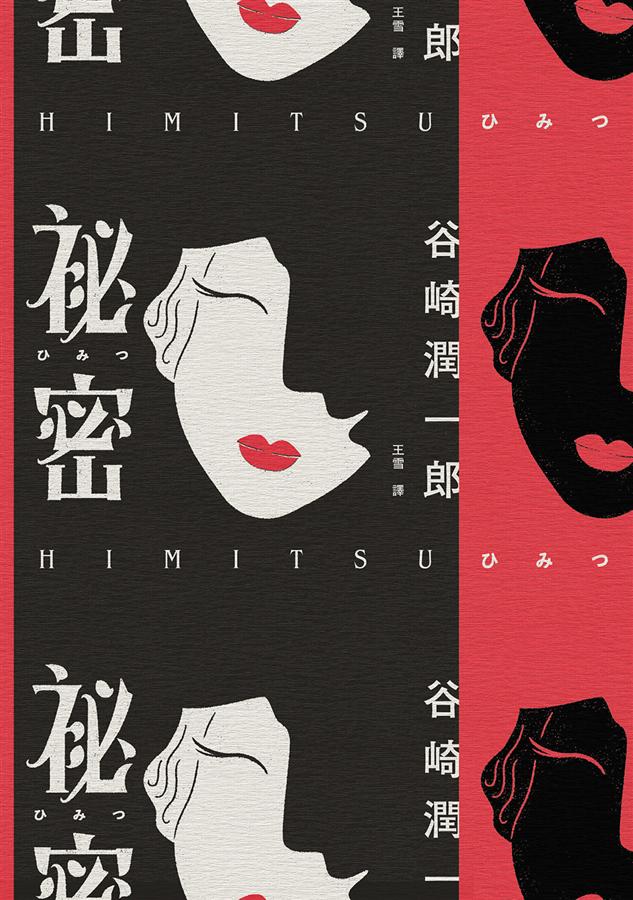

秘密

1911

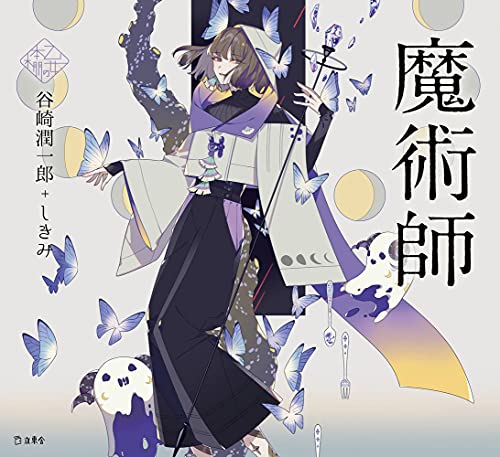

魔術師

2017

人間椅子

2020

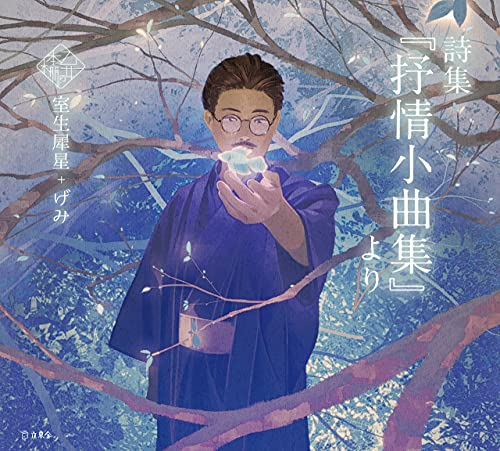

詩集『抒情小曲集』より

2021

Kの昇天 乙女の本棚 (立東舎)

2021

春の心臓 乙女の本棚 (立東舎)

2022

鼠 乙女の本棚 (立東舎)

2022

待つ 乙女の本棚 (立東舎)

2023

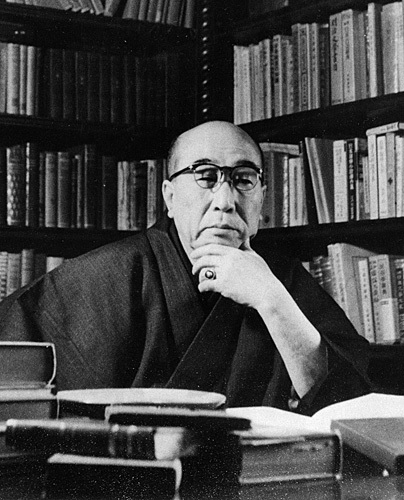

Authors

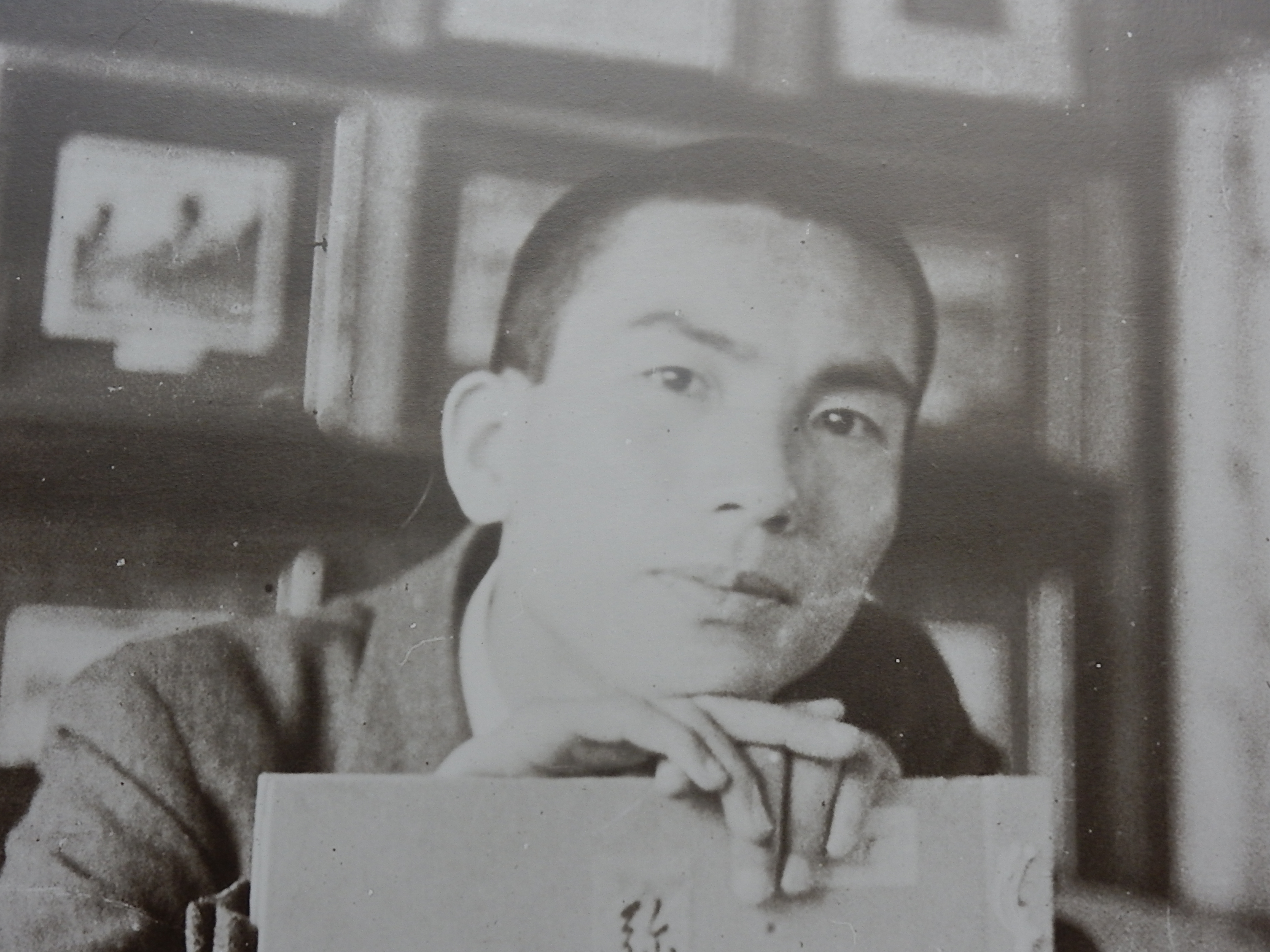

Akutagawa Ryūnosuke (芥川 龍之介) was one of the first prewar Japanese writers to achieve a wide foreign readership, partly because of his technical virtuosity, partly because his work seemed to represent imaginative fiction as opposed to the mundane accounts of the I-novelists of the time, partly because of his brilliant joining of traditional material to a modern sensibility, and partly because of film director Kurosawa Akira's masterful adaptation of two of his short stories for the screen. Akutagawa was born in the Kyōbashi district Tokyo as the eldest son of a dairy operator named Shinbara Toshizō and his wife Fuku. He was named "Ryūnosuke" ("Dragon Offshoot") because he was born in the Year of the Dragon, in the Month of the Dragon, on the Day of the Dragon, and at the Hour of the Dragon (8 a.m.). Seven months after Akutagawa's birth, his mother went insane and he was adopted by her older brother, taking the Akutagawa family name. Despite the shadow this experience cast over Akutagawa's life, he benefited from the traditional literary atmosphere of his uncle's home, located in what had been the "downtown" section of Edo. At school Akutagawa was an outstanding student, excelling in the Chinese classics. He entered the First High School in 1910, striking up relationships with such classmates as Kikuchi Kan, Kume Masao, Yamamoto Yūzō, and Tsuchiya Bunmei. Immersing himself in Western literature, he increasingly came to look for meaning in art rather than in life. In 1913, he entered Tokyo Imperial University, majoring in English literature. The next year, Akutagawa and his former high school friends revived the journal Shinshichō (New Currents of Thought), publishing translations of William Butler Yeats and Anatole France along with original works of their own. Akutagawa published the story Rashōmon in the magazine Teikoku bungaku (Imperial Literature) in 1915. The story, which went largely unnoticed, grew out of the egoism Akutagawa confronted after experiencing disappointment in love. The same year, Akutagawa started going to the meetings held every Thursday at the house of Natsume Sōseki, and thereafter considered himself Sōseki's disciple. The lapsed Shinshichō was revived yet again in 1916, and Sōseki lavished praise on Akutagawa's story Hana (The Nose) when it appeared in the first issue of that magazine. After graduating from Tokyo University, Akutagawa earned a reputation as a highly skilled stylist whose stories reinterpreted classical works and historical incidents from a distinctly modern standpoint. His overriding themes became the ugliness of human egoism and the value of art, themes that received expression in a number of brilliant, tightly organized short stories conventionally categorized as Edo-mono (stories set in the Edo period), ōchō-mono (stories set in the Heian period), Kirishitan-mono (stories dealing with premodern Christians in Japan), and kaika-mono (stories of the early Meiji period). The Edo-mono include Gesaku zanmai (A Life Devoted to Gesaku, 1917) and Kareno-shō (Gleanings from a Withered Field, 1918); the ōchō-mono are perhaps best represented by Jigoku hen (Hell Screen, 1918); the Kirishitan-mono include Hokōnin no shi (The Death of a Christian, 1918), and kaika-mono include Butōkai(The Ball, 1920). Akutagawa married Tsukamoto Fumiko in 1918 and the following year left his post as English instructor at the naval academy in Yokosuka, becoming an employee of the Mainichi Shinbun. This period was a productive one, as has already been noted, and the success of stories like Mikan (Mandarin Oranges, 1919) and Aki (Autumn, 1920) prompted him to turn his attention increasingly to modern materials. This, along with the introspection occasioned by growing health and nervous problems, resulted in a series of autobiographically-based stories known as Yasukichi-mono, after the name of the main character. Works such as Daidōji Shinsuke no hansei(The Early Life of

See Jun'ichirō Tanizaki. 1886年7月24日東京・日本橋生まれ。東京帝国大学国文科中退。既成の倫理観に縛られることなく悪魔的な美と大胆なエロスを追求、独自の耽美的な世界を構築した。1965年7月30日、死去。

Yumeno Kyūsaku (native name: 夢野 久作) was the pen name of the early Shōwa period Japanese author Sugiyama Yasumichi. The pen name literally means "a person who always dreams." He wrote detective novels and is known for his avant-gardism and his surrealistic, wildly imaginative and fantastic, even bizarre narratives. Kyūsaku’s first success was a nursery tale Shiraga Kozō (White Hair Boy, 1922), which was largely ignored by the public. It was not until his first novella, Ayakashi no Tsuzumi (Apparitional Hand Drum, 1924) in the literary magazine Shinseinen that his name became known. His subsequent works include Binzume jigoku (Hell in the Bottles, 1928), Kori no hate (End of the Ice, 1933) and his most significant novel Dogra Magra (ドグラマグラ, 1935), which is considered a precursor of modern Japanese science fiction and was adapted for a 1988 movie. Kyūsaku died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1936 while talking with a visitor at home.

From Niigata, Sakaguchi (坂口安吾) was one of a group of young Japanese writers to rise to prominence in the years immediately following Japan's defeat in World War II. In 1946 he wrote his most famous essay, titled "Darakuron" ("On Decadence"), which examined the role of bushido during the war. It is widely argued that he saw postwar Japan as decadent, yet more truthful than a wartime Japan built on illusions like bushido. Ango was born in 1906, and was the 12th child of 13. He was born in the middle of a Japan perpetually at war. His father was the president of the Niigata Shinbun (Newspaper), a politician, and a poet. Ango wanted to be a writer at 16. He moved to Tokyo at 17, after hitting a teacher who caught him truanting. His father died from brain cancer the following year, leaving his family in massive debt. At 20, Ango taught for a year as a substitute teacher following secondary school. He became heavily involved in Buddhism and went to University to study Indian philosophy, graduating at the age of 25. Throughout his career as a student, Ango was very vocal in his opinions. He wrote various works of literature after graduating, receiving praise from writers such as Makino Shin’ichi. His literary career started around the same time as Japan’s expansion into Manchuria. He met his wife to be, Yada Tsuseko, at 27. His mother died when he was 37, in the middle of World War II. He struggled for recognition as a writer for years before finally finding it with “A Personal View of Japanese Culture” in 1942, and again with “On Decadence” in 1946. That same year, the Emperor formally declared himself a human being, not a god. Ango had a child at 48 with his second wife, Kaji Michio. He died from a brain aneurysm at age 48 in 1955.

Jun'ichirō Tanizaki (谷崎 潤一郎) was a Japanese author, and one of the major writers of modern Japanese literature, perhaps the most popular Japanese novelist after Natsume Sōseki. Some of his works present a rather shocking world of sexuality and destructive erotic obsessions; others, less sensational, subtly portray the dynamics of family life in the context of the rapid changes in 20th-century Japanese society. Frequently his stories are narrated in the context of a search for cultural identity in which constructions of "the West" and "Japanese tradition" are juxtaposed. The results are complex, ironic, demure, and provocative.

Osamu DAZAI (native name: 太宰治, real name Shūji Tsushima) was a Japanese author who is considered one of the foremost fiction writers of 20th-century Japan. A number of his most popular works, such as Shayō (The Setting Sun) and Ningen Shikkaku (No Longer Human), are considered modern-day classics in Japan. With a semi-autobiographical style and transparency into his personal life, Dazai’s stories have intrigued the minds of many readers. His books also bring about awareness to a number of important topics such as human nature, mental illness, social relationships, and postwar Japan.

Atsushi Nakajima (中島敦, Nakajima Atsushi, 5 May 1909 – 4 December 1942) was a Japanese author known for his unique style and self-introspective themes. His major works include "The Moon Over the Mountain" and "Light, Wind and Dreams". During his life he wrote about 20 works, including unfinished works, typically inspired by Classical Chinese stories and his own life experiences.

Japanese profile: 泉 鏡花 Kyōka was born Kyōtarō Izumi on November 4, 1873 in the Shitashinmachi section of Kanazawa, Ishikawa, to Seiji Izumi, a chaser and inlayer of metallic ornaments, and Suzu Nakata, daughter of a tsuzumi hand-drum player from Edo and younger sister to lead protagonist of the Noh theater, Kintarō Matsumoto. Because of his family's impovershed circumstances, he attended the tuition-free Hokuriku English-Japanese School, run by Christian missionaries. Even before he entered grade school, young Kintarō's mother introduced him to literature in picture-books interspersed with text called kusazōshi, and his works would later show the influence of this early contact with such visual forms of story-telling. In April 1883, at ten years old, Kyōka lost his mother, who was 29 at the time. It was a great blow to his young mind, and he would attempt to recreate memories of her in works throughout his literary career. At a friend's boarding house in April 1889, Kyōka was deeply impressed by Ozaki Kōyō's "Amorous Confessions of Two Nuns" and decided to pursue a career in literature. That June he took a trip to Toyama Prefecture. At this time he worked as a teacher in private preparatory schools and spent his free time running through yomihon and kusazōshi. In November of that year, however, Kyōka's aspiration to an artistic career drove him to Tokyo, where he intended to enter the tutelage of Kōyō himself. On 19 November 1891, he called on Kōyō in Ushigome(part of present-day Shinjuku) without prior introduction and requested that he be allowed into the school immediately. He was accepted, and from that time began life as a live-in apprentice. Other than a brief trip to Kanazawa in December of the following year, Kyōka spent all of his time in the Ozaki household, proving his value to Kōyō through correcting his manuscripts and household tasks. Kyōka greatly adored his teacher, thinking of him as a teacher of more than literature, a benefactor who nourished his early career before he gained a name for himself. He felt deeply a personal indebtedness to Kōyō, and continued to admire the author throughout his life.

Japanese profile. Please also see Kyūsaku Yumeno. Chinese profile: 夢野久作. 夢野久作(ゆめの きゅうさく 1889年(明治22年)1月4日 - 1936年(昭和11年)3月11日)は、日本の小説家、禅僧、陸軍少尉、郵便局長。幼名は直樹(なほき)、出家名は杉山泰道(すぎやまやすみち)、禅僧としての名は雲水(うんすい)、雅号は萠圓、柳号は三八、戒名は悟真院吟園泰道居士。現在では、夢久、夢Qなどと呼ばれることもある。夢野久作の筆名は、昔の福岡地方の方言で、夢想家、夢ばかり見る人、という意味を持つ。 日本三大奇書の一つ『ドグラ・マグラ』をはじめ、怪奇色と幻想性の色濃い作風で名高い。ホラー的な作品や、初期には童話もあり、詩や短歌などに長けた。『九州日報』で、今でいう一コマ漫画もかいた。 1936年(昭和11年)3月11日脳溢血で死亡、享年47。

Niimi was born in Yanabe, in the city of Handa, Aichi prefecture, on July 30, 1913. He lost his mother when he was four years old. His literary skill was noticeable at an early age. During his elementary school graduation ceremony, he presented a haiku that impressed most people at the ceremony. At age 18, Niimi moved to Tokyo to enter the Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. He fell sick with tuberculosis while in Tokyo shortly after graduating, and returned to his hometown. He worked there, first as an elementary school teacher, then as a women's high school teacher. He died at age 29. Although not prolific, he shows great talent in all of his writings. His works are known for their accuracy and lively depictions of humans. He is also often compared to Kenji Miyazawa. There is a Niimi Nankichi Memorial Museum in his birthplace, Handa.