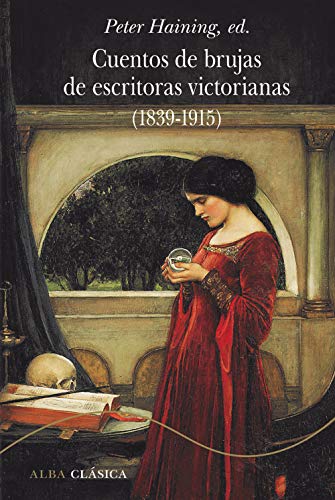

«Y desperté, repitiéndome una y otra vez la misma pregunta: ¿cómo podía una mujer convertirse en tres?». Anna Kingsford En el mundo eminentemente masculino de la sociedad victoriana, volcado en el comercio y la expansión imperial, regido por un orden racionalista y por unos estrictos códigos morales (aunque luego los hombres, pero no las mujeres, pudieran llevar una doble vida), fueron las mujeres quienes se interesaron sobre todo por el fenómeno de la brujería. En Cuentos de brujas de escritoras victorianas (1839-1920) Peter Haining ha reunido sobre este tema crónicas históricas y leyendas tanto como ficciones de escritoras hoy en su mayoría olvidadas pero que sin duda ha valido la pena recuperar. Eliza Lynn Linton estudió profundamente la tradición de la brujería en Inglaterra y Escocia; lo mismo hicieron, en Irlanda, Jane Wilde y, en Gales, Mary Lewes. A su lado, un buen número de autoras –de una tal «H. L.» hasta H. D. Everett− escribieron cuentos de brujas, donde exploraron el conflicto entre religión y ciencia, la condición de la mujer apartada y acosada, la sexualidad asociada a «los espíritus malignos» y—por otro lado—a la intimidación y la explotación, las relaciones entre el amor y la muerte, y la visión de la Naturaleza como una fuerza esencialmente destructora. Estas narraciones tan memorables como imaginativas ilustran tanto el poder de fascinación de la brujería como la mentalidad y la forma de entender lo oscuro de la mujer victoriana.

Authors

Lucie, Lady Duff Gordon was an English writer. She is best known for her Letters from Egypt and Letters from the Cape. She suffered from tuberculosis and in 1851 went to South Africa for the 'climate' which she hoped would help her health, living near the Cape of Good Hope for several years before travelling to Egypt in 1862. In Egypt, she settled in Luxor where she learned Arabic and wrote many letters to her husband and her mother about her observation of Egyptian culture, religion and customs. Many critics regard her as being 'progressive' and tolerant, although she also held problematic views of various racial groups. Her letters home are celebrated for their humor, her outrage at the ruling Ottomans, and many personal stories gleaned from the people around her. In many ways they are also typical of orientalist traveller tales of this time. Most of her letters are to her husband, Alexander Duff-Gordon and her mother, Mrs. Sarah Austin. She married Duff-Gordon in Kensington in 1840. and their daughter, Janet Ann Ross (née Duff Gordon), was born in 1842 and died in 1927. Lady Duff-Gordon was also the author of a number of translations, including one of Wilhelm Meinhold's The Amber Witch. She is one of the characters in the novel The Mistress of Nothing by Kate Pullinger.- Source: Wikipedia

Amelia Ann Blandford Edwards An English novelist, journalist, lady traveller and Egyptologist, born to an Irish mother and a father who had been a British Army officer before becoming a banker. Edwards was educated at home by her mother, showing considerable promise as a writer at a young age. She published her first poem at the age of 7, her first story at age 12. Edwards thereafter proceeded to publish a variety of poetry, stories and articles in a large number of magazines. Edwards' first full-length novel was My Brother's Wife (1855). Her early novels were well received, but it was Barbara's History (1864), a novel of bigamy, that solidly established her reputation as a novelist. She spent considerable time and effort on their settings and backgrounds, estimating that it took her about two years to complete the researching and writing of each. This painstaking work paid off, her last novel, Lord Brackenbury (1880), emerged as a run-away success which went to 15 editions. In the winter of 1873–1874, accompanied by several friends, Edwards toured Egypt, discovering a fascination with the land and its cultures, both ancient and modern. Journeying southwards from Cairo in a hired dahabiyeh (manned houseboat), the companions visited Philae and ultimately reached Abu Simbel where they remained for six weeks. During this last period, a member of Edwards' party, the English painter Andrew McCallum, discovered a previously-unknown sanctuary which bore her name for some time afterwards. Having once returned to the UK, Edwards proceeded to write a vivid description of her Nile voyage, publishing the resulting book in 1876 under the title of A Thousand Miles up the Nile. Enhanced with her own hand-drawn illustrations, the travelogue became an immediate bestseller. Edwards' travels in Egypt had made her aware of the increasing threat directed towards the ancient monuments by tourism and modern development. Determined to stem these threats by the force of public awareness and scientific endeavour, Edwards became a tireless public advocate for the research and preservation of the ancient monuments and, in 1882, co-founded the Egypt Exploration Fund (now the Egypt Exploration Society) with Reginald Stuart Poole, curator of the Department of Coins and Medals at the British Museum. Edwards was to serve as joint Honorary Secretary of the Fund until her death some 14 years later. With the aims of advancing the Fund's work, Edwards largely abandoned her other literary work to concentrate solely on Egyptology. In this field she contributed to the ninth edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica, to the American supplement of that work, and to the Standard Dictionary. As part of her efforts Edwards embarked on an ambitious lecture tour of the United States in the period 1889–1890. The content of these lectures was later published under the title Pharaohs, Fellahs, and Explorer (1891). Amelia Edwards died at Weston-super-Mare, Somerset, on the 15 April 1892, bequeathing her collection of Egyptian antiquities and her library to University College London, together with a sum of £2,500 to found an Edwards Chair of Egyptology. She was buried in St Mary's Church Henbury, Bristol, Wikipedia: Amelia B. Edwards

Pauline Bradford Mackie Hopkins was an American writer of historical fiction. Pauline Bradford Mackie was born in Fairfield, Connecticut on July 5, 1873. Her father, Rev. Andrew Mackie, was an Episcopal clergyman and a scholarly man, from whom she inherited her literary talent. For two years after her graduation from the Toledo High School, she was engaged as a writer on the Toledo Blade. She soon abandoned this for a literary career, and most of her stories appeared in magazines and newspapers. "Mademoiselle de Berny" and "Ye Lyttle Salem Maide" were, after most trying experiences with publishers, printed in book form. "A Georgian Actress" was written in Berkeley, California, where Hopkins had gone with her husband, Dr. Herbert Müller Hopkins (b. Hannibal, Missouri, 1870), who later became the chair of Latin in Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut, where she also wrote two novels of Washington life during the American Civil War.

Beatrice Maude Emelia Huddart Heron-Maxwell was a prolific British author. Her obituary claimed she had written over 700 short stories. She was the daughter of Edward Eastwick, orientalist, diplomat, and Member of Parliament, and Rosina Jane Hunter. Her sister was the novelist Florence Eastwick. She married F. Lane Huddart and they had two daughters. She began her writing career after Huddart's death. In 1891, she married Spencer Horatio Walpole Heron Heron-Maxwell, son of Sir John Heron-Maxwell, 6th Baronet of Springkell. Beatrice Heron-Maxwell published in numerous magazines, including The Bystander, The Harmsworth Monthly Pictorial Magazine, Pall Mall, The Strand, and Tit-Bits. Her The Adventures of a Lady Pearl Broker featured an early female detective, Mollie Delamere. Her novel The Queen Regent was a Ruritanian romance about a young widow who becomes ruler of an island nation. Beatrice Heron-Maxwell was struck by a car in Westbourne Grove, London and died at the hospital two days later.[

Mary Crawford Fraser, usually known as Mrs. Hugh Fraser, was a writer noted for her various memoirs and historical novels. She was the daughter of American sculptor Thomas Crawford and Louisa Cutler Ward. She was sister to novelist Francis Marion Crawford and the niece of Julia Ward Howe (the American abolitionist, social activist, and poet most famous as the author of "The Battle Hymn of the Republic"). As the wife of British diplomat, she followed her husband to his postings in Peking, Vienna, Rome, Santiago, and Tokyo. In Rome in 1884, over the opposition of her mother, she converted to Catholicism. In 1889, her husband Hugh Fraser was posted to Japan as "Minister Plenipotentiary and Envoy Extraordinary (head of the British Legation) to Japan—a diplomatic ranking just below that of full Ambassador. before the establishment of full and equal relations between Britain and Japan which Fraser was, in fact, negotiating. A month before the signing of the final treaty, her husband died suddenly in 1894, leaving her a widow after twenty years of marriage. Still under her married name of Mrs. Hugh Fraser, she was the author of Palladia (1896), The Looms of Time (1898), The Stolen Emperor (1904), The Satanist (1912, with J. I. Stahlmann, the pseudonym of one of her sons, John Crawford Fraser).