Authors

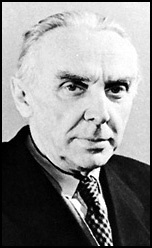

Vsevolod Vyacheslavovich Ivanov (Russian: Всеволод Вячеславович Иванов; February 24, 1895 in Lebyazhye, now in Pavlodar Oblast – August 15, 1963, Moscow) was a notable Soviet writer praised for the colourful adventure tales set in the Asiatic part of Russia during the Civil War. Ivanov was born in Northern Kazakhstan to a teacher's family. When he was a child Vsevolod ran away to become a clown in a travelling circus. His first story, published in 1915, caught the attention of Maxim Gorky, who advised Vsevolod throughout his career. Ivanov joined the Red Army during the Civil War and fought in Siberia. This inspired his short stories, Partisans (1921) and Armoured Train (1922). In 1922 Ivanov joined the literary group Serapion Brothers. Other members included Nikolay Tikhonov, Mikhail Zoshchenko, Victor Shklovsky, Veniamin Kaverin, and Konstantin Fedin. Ivanov's first novels, Colored Winds (1922) and Azure Sands (1923), were set in Asiatic part of Russia and gave rise to the genre of ostern in Soviet literature. His novella Baby was acclaimed by Edmund Wilson as the finest Soviet short story ever. Later, Ivanov came under fire from Bolshevik critics who claimed his works were too pessimistic and that it was not clear whether the Reds or Whites were the heroes. In 1927 Ivanov rewrote his short story, the Armoured Train 14-69 into a play. This time, the play highlighted the role of the Bolsheviks in the Civil War. After that, his writings saw a marked decline in quality, and he never managed to produce anything equal to his early efforts. Among his later works, which conformed to the requirements of Socialist Realism, are the Adventures of a Fakir (1935) and The Taking of Berlin (1945). During the Second World War, Ivanov worked as a war correspondent for Izvestia. Vsevolod's son Vyacheslav Vsevolodovich Ivanov became one of the leading philologists and Indo-Europeanists of the late 20th century. Vsevolod adopted Isaak Babel's illegitimate child Emmanuil when he married Babel's one time mistress Tamara Kashirina. Emmanuil's name was changed to "Mikhail Ivanov" and he later became a noted artist.

Valentin Petrovich Kataev (Russian: Валентин Катаев; also spelled Katayev or Kataiev) was a Russian and Soviet novelist and playwright who managed to create penetrating works discussing post-revolutionary social conditions without running afoul of the demands of official Soviet style. Kataev is credited with suggesting the idea for the Twelve Chairs to his brother Yevgeni Petrov and Ilya Ilf. In return, Kataev insisted that the novel be dedicated to him, in all editions and translations. Kataev's relentless imagination, sensitivity, and originality made him one of the most distinguished Soviet writers. Kataev was born in Odessa (then Russian Empire, now Ukraine) into the family of a teacher and began writing while he was still in gimnaziya (high school). He did not finish the gimnaziya but volunteered for the army in 1915, serving in the artillery. After the October Revolution he was mobilized into the Red Army, where he fought against General Denikin and served in the Russian Telegraph Agency. In 1920, he became a journalist in Odessa; two years later he moved to Moscow, where he worked on the staff of The Whistle (Gudok), where he wrote humorous pieces under various pseudonyms. His first novel, The Embezzlers (Rastratchiki, 1926), was printed in the journal "Krasnaya Nov". A satire of the new Soviet bureaucracy in the tradition of Gogol, the protagonists are two bureaucrats "who more or less by instinct or by accident conspire to defraud the Soviet state". The novel was well received, and the seminal modernist theatre practitioner Constantin Stanislavski asked Kataev to adapt it for the stage. It was produced at the world-famous Moscow Art Theatre, opening on 20 April 1928. A cinematic adaptation was filmed in 1931. His comedy Quadrature of the circle (Kvadratura kruga, 1928) satirizes the effect of the housing shortage on two married couples who share a room. His novel Time, Forward! (Vremya, vperyod!, 1932) describes workers' attempts to build the huge steel plant at Magnitogorsk in record time. Its title was taken from a poem by Vladimir Mayakovsky. its theme is the speeding up of time in the Soviet Union where the historical development of a century must be completed in ten years". The heroes are described as "being unable to trust such a valuable thing as time, to clocks, mere mechanical devices." Kataev adapted it as a screenplay, which filmed in 1965. A White Sail Gleams (Beleyet parus odinoky, 1936) treats the 1905 revolution and the Potemkin uprising from the viewpoint of two Odessa schoolboys. In 1937, Vladimir Legoshin directed a film version, which became a classic children's adventure. Kataev wrote its screenplay and took an active part in the filming process, finding locations and acting as an historical advisor. Many of his contemporaries considered the novel to be a prose poem.

Born July 5 (17), 1891, in Kherson; died Jan. 7, 1959, in Moscow. Soviet Russian writer and playwright. Son of a literature teacher. Lavrenev graduated in law from Moscow University in 1915. He fought in World War I (1914–18) and in the Civil War (1918–20). His literary debut came with the publication of his poetry in 1911, and his first story was published in 1924. The novellas The Wind, The Forty-first (both 1924; made into motion pictures in 1927 and 1956), and A Story About Something Simple (1927) were devoted to events of the Great October Socialist Revolution and the Civil War. Lavrenev was drawn to heroic characters and the elemental, romantic aspect of heroism (the wind image). In the late 1920’s, Lavrenev wrote primarily about the intelligentsia, the people, and the Revolution (the novella The Seventh Fellow-traveler, 1927), as well as the fate of culture and the arts (the novella Wood Engraving, 1928). His prose is dramatic, with intricate plotting and character development through direct action. The play Break (1927; staged by many theaters at home and abroad) epitomized Lavrenev’s artistic concerns. He treated the Revolution and the heroic character in a thorough and new way, depicting heroism in its everyday rather than its extraordinary manifestations. This attitude was reflected in such later works as the novella Big Earth (1935) and the plays The Song of the Black Sea Sailors (1943) and To Those in the Sea! (1945). Lavrenev criticized bourgeois society in the novel The Fall of the Itl’ Republic (1925), the novella A Strategic Mistake (1934), and journalistic articles, pamphlets, and feuilletons. He received the State Prize of the USSR (1946 and 1950) and was awarded two orders and several medals. WORKS Sobr. sock, vols. 1–6. Introduction by E. Starikova. Moscow, 1963–65. REFERENCES Vishnevskaia, I. Boris Lavrenev. Moscow, 1962. Kardin, V. “Prostye veshchi (Zametki o proze Borisa Lavreneva).” Novyi mir, 1969, no. 7. D. P. MURAV’EV The Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition (1970-1979). © 2010 The Gale Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

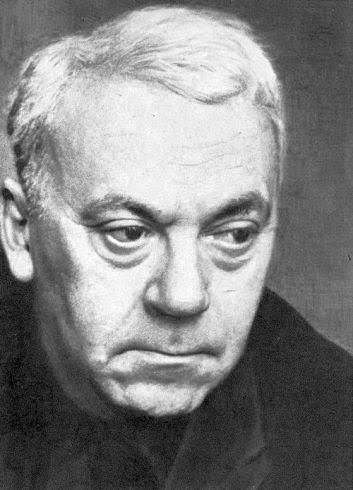

Konstantin Aleksandrovich Fedin (Russian: Константин Александрович Федин) was a Russian novelist and literary functionary. Born in Saratov of humble origins, Fedin studied in Moscow and Germany and was interned there during World War I. After his release he worked as an interpreter in the first Soviet embassy in Berlin. On returning to Russia he joined the Bolsheviks and served in the Red Army; after leaving the Party in 1921 he joined the literary group called the Serapion Brothers, who supported the Revolution but wanted freedom for literature and the arts. His first story, "The Orchard," was published in 1922, as was his play Bakunin v Drezdene (Bakunin in Dresden). His first two novels are his most important; Goroda i gody (1924; tr. as Cities and Years, 1962, "one of the first major novels in Soviet literature") and Bratya (Brothers, 1928) both deal with the problems of intellectuals at the time of the October Revolution, and include "impressions of the German bourgeois world" based on his wartime imprisonment. His later novels include Pokhishchenie Evropy (The rape of Europe, 1935), Sanatorii Arktur (The Arktur sanatorium, 1939), and the historical trilogy, Pervye radosti (First joys, 1945), Neobyknovennoe leto (An unusual summer, 1948), and Kostyor (The fire, 1961-67). He also wrote a memoir Gorky sredi nas (Gorky among us, 1943). Edward J. Brown sums him up as follows: "Fedin, while he is probably not a great writer, did possess in a high degree the talent for communicating the atmosphere of a particular time and place. His best writing is reminiscent re-creation of his own experiences, and his memory is able to select and retain sensuous elements of long-past scenes which render their telling a rich experience." From 1959 until his death he served as chair of the Union of Soviet Writers.

Korney Ivanovich Chukovsky (Russian: Корней Иванович Чуковский) was one of the most popular children's poets in the Russian language. His catchy rhythms, inventive rhymes and absurd characters have invited comparisons with the American children's author Dr. Seuss. Chukovsky's poems Tarakanishche ("The Monster Cockroach"), Krokodil ("The Crocodile"), Telefon ("The Telephone") and Moydodyr ("Wash-'em-Clean") have been favorites with many generations of Russophone children. Lines from his poems, in particular Telefon, have become universal catch-phrases in the Russian media and everyday conversation. He adapted the Doctor Dolittle stories into a book-length Russian poem as Doktor Aybolit ("Dr. Ow-It-Hurts"), and translated a substantial portion of the Mother Goose canon into Russian as Angliyskiye Narodnyye Pesenki ("English Folk Rhymes"). He was also an influential literary critic and essayist. (from: wikipedia) For Russian version of same author: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show...

Russian writer Aleksei Maksimovich Peshkov (Russian: Алексей Максимович Пешков) supported the Bolshevik revolution of 1917 and helped to develop socialist realism as the officially accepted literary aesthetic; his works include The Life of Klim Samgin (1927-1936), an unfinished cycle of novels. This Soviet author founded the socialist realism literary method and a political activist. People also nominated him five times for the Nobel Prize in literature. From 1906 to 1913 and from 1921 to 1929, he lived abroad, mostly in Capri, Italy; after his return to the Soviet Union, he accepted the cultural policies of the time.

Yuri Pavlovich German (Russian: Ю́рий Па́влович Ге́рман) (April 4 [O.S. March 22] 1910 – January 16, 1967) was a Soviet Russian writer, playwright, screenwriter, and journalist. German was born in Riga (then part of the Russian Empire) and accompanied his father, an artillery officer, during the Civil War. He graduated from high school in Kursk and studied at the Technical School of Performing Arts in Leningrad in 1929. At age 17, he wrote the novel Rafael iz parikmakherskoi (Raphael of the barbershop), published in 1928, but did not consider himself a professional writer until he published the novel Vstuplenie (Entry), which met with the approval of Maxim Gorky, in 1931. In 1936, together with director Sergei Gerasimov, he wrote the screenplay for the movie Semero smelykh (The courageous seven), about researchers in the Arctic; among his other screenplays were Pirogov (1947) and Belinsky (1951), both directed by Grigori Kozintsev, and Delo Rumyantseva (The Rumyantsev case, 1955), directed by Iosif Kheifits. During World War II German was a war correspondent for TASS and the Soviet Information Bureau with the Northern Fleet. He spent the entire war in the north; from Arkhangelsk he often flew to Murmansk or Kandalaksha, living in the Arctic for months on end, traveling to the front, visiting forward positions, and spending time on the warships of the Northern Fleet. During this time he wrote essays and articles for TASS, and still found time for short stories and novels. During the war he wrote the short novels Bi kheppi! (Be happy!), Attestat (The certificate), Studyonoe more (The frozen sea), and Daleko na Severe (The far north) and the plays Za zdorov'e togo, kto v puti (To the health of the man on the road) and Beloe more (White Sea). He was a member of the Communist Party from 1958. After the war he wrote a historical novel about the era of Peter the Great, Rossiya molodaya (Young Russia, 1952). From his novels and short stories his son Aleksei German made the films Proverka na dorogakh (Trial on the road, or road check, from the novel Operatsiya "S Novym godom") and Moi drug Ivan Lapshin (My Friend Ivan Lapshin), and Semyon Aranovich made the film Torpedonostsy (Torpedo bombers). German died in Leningrad and was buried at the Bogoslovskoe Cemetery. AKA: Юрий Герман (Russian) Jurijs Germans (Latvian)

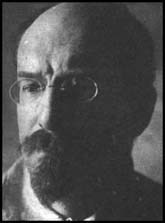

Vladimir Dmitriyevich Bonch-Bruyevich (Russian: Владимир Дмитриевич Бонч-Бруевич) (28 June [O.S. 16 June] 1873 – 14 July 1955) was a Soviet politician, revolutionary, historian, writer and Old Bolshevik. He was Vladimir Lenin's personal secretary. Vladimir Dmitriyevich Bonch-Bruyevich was born in Moscow to a land surveyor family who came from the Mogilev province and belonged to the nobility of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania. He was a younger brother of the future Soviet military commander Mikhail Dmitriyevich Bonch-Bruyevich. At the age of ten, he was sent to the Moscow Institute of Surveying and graduated from the school of land surveying. In 1889, he was arrested for taking part in a student demonstration, and banished to Kursk. He returned to Moscow in 1892 and entered the "Moscow Workers' Union" and distributed illegal literature. From 1895 he was active in the social-democratic circles. In 1896 he emigrated to Switzerland and organized shipments of Russian revolutionary literature and printing equipment and became an active member of Iskra.

Alexander Alexandrovich Fadeyev (Russian: Александр Алексaндрович Фадеев) was a Soviet writer, one of the co-founders of the Union of Soviet Writers and its chairman from 1946 to 1954. From 1908 to 1912 he lived in Chuguyevka, Primorsky Krai. He took part in the guerrilla movement against the Japanese interventionists and the White Army during the Russian Civil War. In 1927, he published the novel The Rout (also known as The Nineteen), in which he described youthful guerrilla fighters. In 1945 he wrote the novel Young Guard (based upon real events of World War II) about the underground anti-fascist Komsomol organization named Young Guard, which fought against the Nazis in the occupied city Krasnodon (in the Ukrainian SSR). For this novel, Fadeyev was awarded the Stalin Prize (1946). In 1948, a Soviet film The Young Guard, based on the book, was released, and later revised in 1964 to correct inaccuracies in the book. Fadeyev was a champion of Joseph Stalin, proclaiming him "the greatest humanist the world has ever known". During the 1940s, he actively promoted Zhdanovshchina, a campaign of criticism and persecution against many of the Soviet Union's foremost composers. However, he was a friend of Mikhail Sholokhov. Fadeyev married a famous stage actress, Angelina Stepanova (1905–2000). In the last years of his life Fadeyev became an alcoholic. Some sources claim, that this was mostly due to the denunciation of Stalinism during the Khrushchev Thaw. He eventually committed suicide at his dacha in Peredelkino, leaving a dying letter, from which one can see Fadeyev's strictly negative attitude to new leaders of the Party. His death occasioned an epigram by Boris Pasternak, his neighbor. Alexander Fadeyev is buried in the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow.

Drabkina Elizaveta Yakovlevna was a Soviet writer. Until 1905 she lived in Belgium. Father Gusev Sergei Ivanovich, in 1886 joined the Union of Struggle for the Liberation of the Working Class. Participated in the preparation of the 2nd Congress of the RSDLP in Brussels, an unshakable Bolshevik. In 1917, secretary of the military revolutionary committee of the Petrograd Soviet. During the civil war, in leading positions in the Red Army. He died in 1933. Mother Theodosia Ilyinichna Drabkina, an old Bolshevik woman, more than once performed Lenin's tasks. Party nickname - Natasha, in the party since 1902, the prototype of the propagandist Natasha in M. Gorky's novel "Mother". In 1905 he was a member of the militant organization of the Bolshevik Party. In the days of the December armed uprising, she carried the fuses of bombs and fuses to Moscow. She worked at the Foreign Literature publishing house. Elizaveta graduated from high school in 1917, in April 1917 she joined the Bolshevik Party. Machine gunner in the Red Army. She took part in the storming of the Winter Palace. She fought on the southern front and was awarded a gold watch. She worked as Sverdlov's secretary until his death. Participated in the suppression of the Kronstadt uprising. 1923-1927 graduated from the history department of the Institute of the Red Professors. In 1925-1926 she visited Germany and France. In 1926 she joined the Trotskyist opposition. In March 1928 in Kiev expelled from the party. In January 1929 she left for her husband (Babenets Alexander Ivanovich). She was sentenced to 3 years of exile, in fact she did not serve. In August 1929 she broke with the Trotskyist opposition. In 1930 she was reinstated in the party, again expelled in August 1936. In December 1936 she was arrested for participating in the Trotskyist organization. She was sentenced to 5 years in prison, then on revision under Art. 17-58-8, 7, 10, 11 of the Criminal Code a new term of 15 years in labor camps and 5 years of deprivation of political rights. The Supreme Court of Art. 58-7 removed. She was serving a sentence in the Norillag. She worked at a coal mine, then as a translator, proofreader, and legal adviser. She was repeatedly awarded. Together with A. Agranovsky and Milchakov, she organized a secret circle in the camp to study Marxism-Leninism. In the camp they beat her so badly that she almost went deaf. Released, went to the mainland. Did not work. She returned to Norilsk, where she returned in September 1948. She worked as an economist in the office "Thermal insulation". She worked together with N.P. Vsesvyatskaya. When she was talking, she put a tube from a newspaper to her ear to hear. Arrested in January 1949. Convicted on 20.04.1949 by the OSO MGB of the USSR for exile in Norilsk. After her release, she returned to Moscow. She was engaged in literary work, wrote pro-communist works. In works of fiction and memoir (Black Crackers, 1957-60; Winter Pass, 1968; Reflections in Gorki, Kronstadt, 1921, both published in 1987), some facts that were hushed up are first reported about the post-revolutionary years official historiography.

Librarian Note: There is more than one author in the Goodreads database with this name. American journalist John Silas Reed, a correspondent of World War I, recounted an experience in Petrograd during the revolution of October 1917 in Ten Days That Shook the World (1919) and, after returning to the United States, cofounded the Communist labor party in 1919; people buried his body in the Kremlin, the citadel, housing the offices of the Russian government and formerly those of the Soviet government, in Moscow. This poet and Communist activist first gained prominence as a war correspondent during the Mexican revolution for Metropolitan magazine and during World War I for the magazine The Masses. People best know his coverage. Reed supported the Soviet takeover of Russia and even briefly took up arms to join the Red guards in 1918. He expected a similar Communist revolution in the United States with the short-lived organization. He died in Moscow of spotted typhus. At the time of his death, he perhaps soured on the Soviet leadership, but the Soviet Union gave him burial of a hero, one of only three Americans at the Kremlin wall necropolis.