Books in series

The Christian Religion, as Professed by a Daughter of the Church of England

2013

Memoirs Of Sophia

Electress Of Hanover, 1630-1680

2013

"My Rare Wit Killing Sin"

Poems of a Restoration Courtier

2013

Russian Women Poets of the Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries

A Bilingual Edition

2014

Poems, Emblems, and The Unfortunate Florinda (Volume 32)

2014

Complete Poems

A Bilingual Edition

2014

The Wealth of Wives

A Fifteenth-Century Marriage Manual

1415

Orphan Girl

A Transaction, or an Account of the Entire Life of an Orphan Girl by way of Plaintful Threnodies in the Year 1685. The Aesop Episode ... in Early Modern Europe: The Toronto Series)

2016

Ippolita Maria Sforza

Duchess and Hostage in Renaissance Naples: Letters and Orations

2017

Letter of Othea to Hector

1970

Mirtilla

A Pastoral

2013

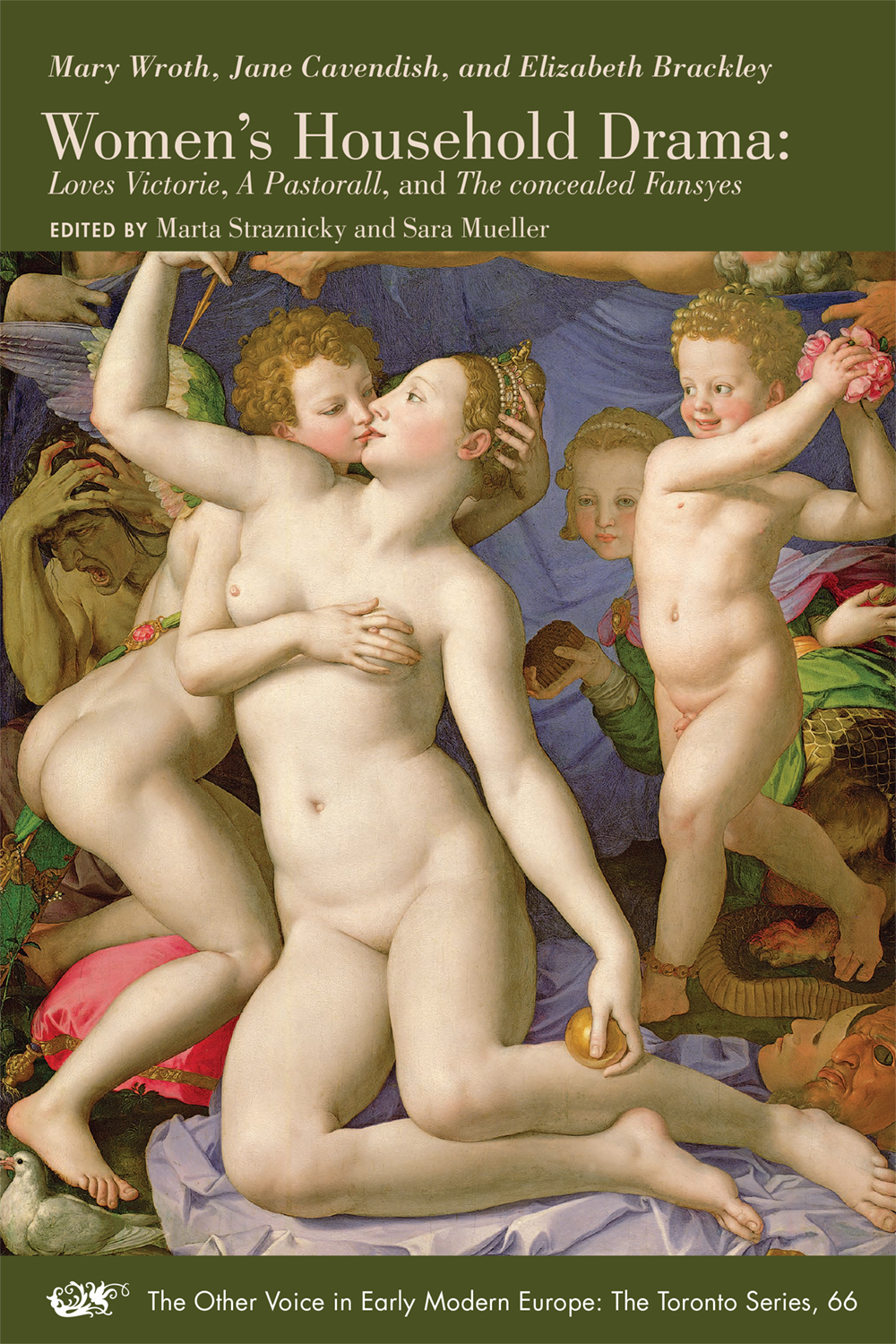

Women's Household Drama

Loves Victorie, A Pastorall, and The concealed Fansyes

2018

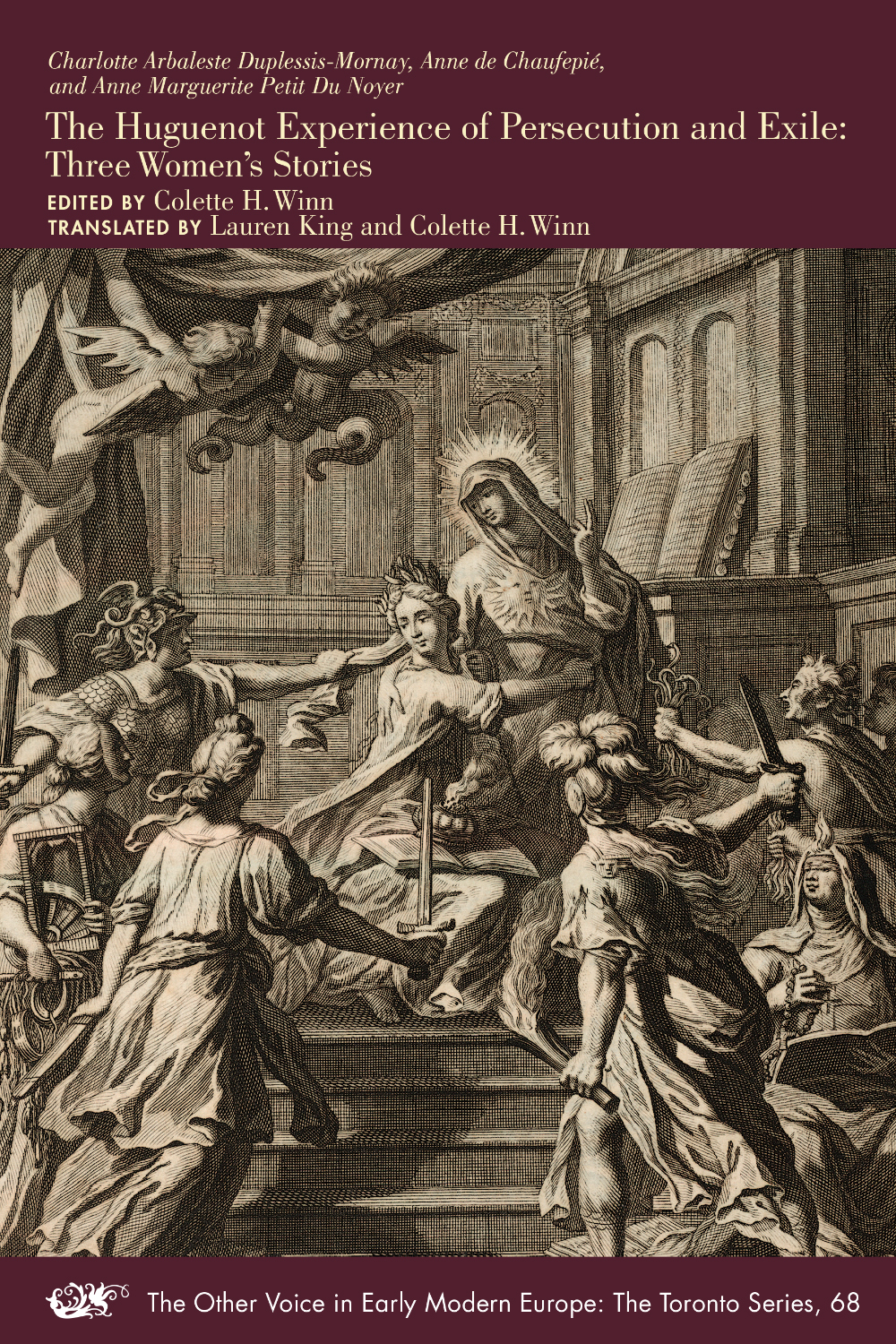

Charlotte Arbaleste Duplessis-Mornay, Anne de Chaufepié, and Anne Marguerite Petit Du Noyer

The Huguenot Experience of Persecution and Exile: Three Women’s Stories

2019

Arcangela Tarabotti

Antisatire: In Defense of Women Against Francesco Buoninsegni

2019

"The God of Love’s Letter" and "The Tale of the Rose"

A Bilingual Edition. With Jean Gerson, “A Poem on Man and Woman,” Translated from the Latin by ... in Early Modern Europe: The Toronto Series)

2021

Authors

1660–1685 English poet and painter

Christine de Pizan (also seen as de Pisan) (1363–c.1434) was a writer and analyst of the medieval era who strongly challenged misogyny and stereotypes that were prevalent in the male-dominated realm of the arts. De Pizan completed forty-one pieces during her thirty-year career (1399–1429). She earned her accolade as Europe’s first professional woman writer (Redfern 74). Her success stems from a wide range of innovative writing and rhetorical techniques that critically challenged renowned male writers such as Jean de Meun who, to Pizan’s dismay, incorporated misogynist beliefs within their literary works. In recent decades, de Pizan's work has been returned to prominence by the efforts of scholars such as Charity Cannon Willard and Earl Jeffrey Richards. Certain scholars have argued that she should be seen as an early feminist who efficiently used language to convey that women could play an important role within society, although this characterisation has been challenged by other critics who claim either that it is an anachronistic use of the word, or that her beliefs were not progressive enough to merit such a designation

Mary Astell was an English feminist writer. Her advocacy of equal educational opportunities for women has earned her the title "the first English feminist." Few records of Mary Astell's life have survived. As biographer Ruth Perry explains, "as a woman she had little or no business in the world of commerce, politics, or law. She was born, she died; she owned a small house for some years; she kept a bank account; she helped to open a charity school in Chelsea: these facts the public listings can supply." Only four of her letters were saved and these because they had been written to important men of the period. Researching the biography, Perry uncovered more letters and manuscript fragments, but she notes that if Astell had not written to wealthy aristocrats who could afford to pass down entire estates, very little of her life would have survived. Mary Astell was born in Newcastle upon Tyne on 12 November 1666, to Peter and Mary (Errington) Astell. Her parents had two other children, William, who died in infancy, and Peter, her younger brother. Her family was upper-middle-class and lived in Newcastle throughout her early childhood. Her father was a conservative royalist Anglican who managed a local coal company. As a woman, Mary received no formal education, although she did receive informal education from her uncle, an ex-clergyman whose bouts with alcoholism prompted his suspension from the Church of England. Mary's father died when she was twelve, leaving her without a dowry. With the remainder of the family finances invested in her brother's higher education, Mary and her mother relocated to live with Mary's aunt. After the death of her mother and aunt in 1688, Mary moved to London. Her location in Chelsea meant that Astell was fortunate enough to become acquainted with a circle of literary and influential women (including Lady Mary Chudleigh, Elizabeth Thomas, Judith Drake, Elizabeth Elstob, and Lady Mary Wortley Montagu), who assisted in the development and publication of her work. She was also in contact with the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Sancroft, who was known for his charitable works; Sancroft assisted Astell financially and furthermore introduced her to her future publisher. Astell died in 1731, a few months after a mastectomy to remove a cancerous right breast. In her last days, she refused to see any of her acquaintances and stayed in a room with her coffin, thinking only of God. She is remembered now for her ability to debate freely with both contemporary men and women, and particularly her groundbreaking methods of negotiating the position of women in society by engaging in philosophical debate (Descartes was a particular influence) rather than basing her arguments in historical evidence as had previously been attempted. Descartes' theory of dualism, a separate mind and body, allowed Astell to promote the idea that women as well as men had the ability to reason, and subsequently they should not be treated so poorly: "If all Men are born Free, why are all Women born Slaves?"