Books in series

Preface and Introduction to a Contribution to the Critque of Political Economy

1968

Elogio dell'antropologia

Lezione inaugurale al Collège de France

1960

Excedente económico e irracionalidad capitalista

1968

La filosofía como arma de la revolución

1968

Escritos económicos

1969

Francia 1968

¿Una revolución fallida?

2025

Teoría Marxista del Partido Político

1969

Materialismo histórico y materialismo dialéctico

1969

Sartre y Marx

1969

Teoría marxista del imperialismo

1969

Dialéctica marxista e historicismo

2025

The Mass Strike

1906

La revolución palestina y el conflicto árabe-israelí

1970

El marxismo de Trotsky

1970

El joven Lukács

1970

The New Economics

1926

Gramsci Y Las Ciencias Sociales

1972

Pre-Capitalist Economic Formations

1965

Imperialism and World Economy

1917

Revolución política o poder burocrático. I. Polonia

1971

La Revolución Cultural China

1971

Imperialismo y comercio internacional

1971

The Cultural Revolution at Peking University

1969

Los bolcheviques y la revolución de octubre

1972

Economics of the transformation period

1920

Materiales para la historia de América Latina

1972

Historical Materialism

A System of Sociology

1921

La división capitalista del trabajo

1972

Consejos obreros y democracia socialista

1972

El gran debate (1924-1926), I. La revolución permanente

1963

Einführung in die Nationalökonomie

1925

El gran debate 1924-26, II. El socialismo en un solo país

1972

On Colonialism

1973

El concepto de formación económico social

1973

Modos de producción en América Latina

1973

Revolución socialista y antiparlamentarismo

1973

Lenin as Philosopher

1938

Los cuatro primeros congresos de la Internacional Comunista. Primera parte

1973

Economía y política en la acción sindical

1974

¿Qué es la socialización? Un programa de socialismo práctico

1973

Teoría del proceso de transición

1973

Los cuatro primeros congresos de la Internacional Comunista. Segunda parte

1934

Hegemonía y Dominación En El Estado Moderno

1969

Contribución a la crítica de las teorías modernas de las crisis

1978

El imperialismo y la acumulación de capital

1975

La internacional comunista y el problema colonial

1967

Essays on Marx's Theory Of Value

1923

Escritos políticos (1917-1933)

La teoria general del marxismo en Gramsci

1977

V Congreso de la Internacional Comunista. Primera parte

1975

V Congreso de la Internacional Comunista. Segunda parte

1975

Economic Theory of the Leisure Class

1970

Ethics and the Materialist Conception of History

2002

Ludwig Feuerbach And the Outcome of Classical German Philosophy

1886

Mariátegui Y Los Orígenes Del Marxismo Latinoamericano

1978

Huelga general y socialismo

1975

Debate sobre la huelga de masas (Primera parte)

1975

Debate sobre la huelga de masas (Segunda parte)

1976

On historical materialism

1975

La construcción del socialismo

vía china o modelo soviético

1975

VI Congreso de la Internacional Comunista. Primera parte

1977

VI Congreso de la Internacional Comunista. Segunda parte

1978

La revolución social. El camino del poder

1978

La cuestión nacional y la formación de los estados

1980

History of Bolshevism from Marx to the First Five Years' Plan

1932

El desarrollo industrial de Polonia y otros escritos sobre el problema nacional

1979

Imperio y colonia. Escritos sobre Irlanda

1979

La Segunda Internacional y el problema nacional y colonial (Primera parte)

1978

La Segunda Internacional y el problema nacional y colonial (Segunda Parte)

1978

Clausewitz en el pensamiento marxista

1979

Fascismo, democracia y frente popular. VII Congreso de la Internacional Comunista

1984

El sistema de Marx. Un aporte para su construcción

1929

¿Derrumbe del capitalismo o sujeto revolucionario?

1978

Ensayos sobre la teoría de la crisis. Dialéctica y metodología en "El Capital"

1971

La Internacional Comunista y América Latina. La sección venezolana

1978

The National Question

Selected Writings by Rosa Luxemburg (Monthly Review Press Classic Titles)

1976

Class Struggle and the Jewish Nation

Selected Essays in Marxist Zionism

1972

La crisis del capitalismo en los años '20. Análisis económico y debate estratégico en la Tercera Internacional

1978

Democracia y socialismo

Una contribución a la historia política de los últimos 150 años

1939

Aníbal Ponce--el marxismo sin nación?

1983

Engels and the "Nonhistoric" Peoples

The National Question in the Revolution of 1848

1979

Authors

French historian. He had taught for many years at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS) in Paris. Paris had an original and atypical research path - at the crossroads of various disciplines. A curious and polyglot spirit, his interests in Italian politics and culture intersected with an interest in Latin American history and culture. A work of great commitment that took up many years of Robert's intellectual life was also the complete translation of the notebooks from Gramsci's prison, directed and edited by him with great originality, as evidenced by the richness of the critical apparatus of notes as well as his wide-ranging introduction to the last of the five volumes published in Gallimard's prestigious Bibliothèque de philosophie. Finally, as regards Latin America, in addition to the writings relating to Mariategui and his universe, in the last years of his active life he was working on a Dictionnaire biographique du mouvement ouvrier d 'Amérique latine.

Alain Badiou, Ph.D., born in Rabat, Morocco in 1937, holds the Rene Descartes Chair at the European Graduate School EGS. Alain Badiou was a student at the École Normale Supérieure in the 1950s. He taught at the University of Paris VIII (Vincennes-Saint Denis) from 1969 until 1999, when he returned to ENS as the Chair of the philosophy department. He continues to teach a popular seminar at the Collège International de Philosophie, on topics ranging from the great 'antiphilosophers' (Saint-Paul, Nietzsche, Wittgenstein, Lacan) to the major conceptual innovations of the twentieth century. Much of Badiou's life has been shaped by his dedication to the consequences of the May 1968 revolt in Paris. Long a leading member of Union des jeunesses communistes de France (marxistes-léninistes), he remains with Sylvain Lazarus and Natacha Michel at the center of L'Organisation Politique, a post-party organization concerned with direct popular intervention in a wide range of issues (including immigration, labor, and housing). He is the author of several successful novels and plays as well as more than a dozen philosophical works. Trained as a mathematician, Alain Badiou is one of the most original French philosophers today. Influenced by Plato, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Jacques Lacan and Gilles Deleuze, he is an outspoken critic of both the analytic as well as the postmodern schools of thoughts. His philosophy seeks to expose and make sense of the potential of radical innovation (revolution, invention, transfiguration) in every situation.

Roman Osipovich Rosdolsky (Russian: Роман Осипович Роздольский; Ukrainian: Рома́н О́сипович Роздо́льський Roman Osipovič Rozdol's'kyj) was an important Marxian scholar and political revolutionary. As a youth, Rosdolsky was a member of the Ukrainian socialist Drahomanov Circles. He was drafted in the imperial army in 1915, and edited with Roman Turiansky the journal Klyči in 1917. He was a founder of the International Revolutionary Social Democracy (IRSD) and studied law in Prague. During World War I he founded the antimilitaristic "Internationale Revolutionäre Sozialistische Jugend Galiziens" (International Revolutionary Socialist Youth of Galizia). He became a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Eastern Galicia, representing its émigré organization 1921-1924 and a leading publicist of the Vasylkivtsi faction of the Ukrainian Communists. In 1925, he refused to condemn Trotsky and his Left Opposition, and was later, at the end of the 1920s, expelled from the Communist Party. In 1926-1931, he was correspondent in Vienna of the Marx-Engels Institute in Moscow, searching for archival materials. At that time, in 1927, he met his wife Emily. When the labour movement in Austria suffered repression, he emigrated in 1934 back to L'viv, where he worked at the university as lecturer. He published the Trotskyist periodical Žittja i slovo 1934-1938, and was arrested by the Gestapo in 1942, but survived internment for three years in the concentration camps of Auschwitz, Ravensbrück and Oranienburg. He emigrated to the USA in 1947, and worked there as independent scholar - failing to obtain a university post. He published also under pseudonyms such as "Roman Prokopovycz", "P.Suk.", "Tenet" and "W.S.". Rosdolsky is mainly known in the Anglo-Saxon world for his careful scholarly exegesis The Making of Marx's Capital, a collection of essays some which had previously been published, which overturned many previous interpretations of Das Kapital. Yet he published much more, especially on historical topics (see below). During his life, he corresponded with numerous well known Marxist writers including Isaac Deutscher, Ernest Mandel, Paul Mattick, and Karl Korsch. Mandel called Rosdolsky's work on the National Question the only Marxist criticism of Marx himself.

President of the Fondazione Istituto Gramsci (Rome) and of the scientific commission in charge of editing the writings of Antonio Gramsci. A historian of political thought, he has dedicated numerous studies to the Gramscian corpus, among which stand out Gramsci e Togliatti (1991), Appuntamenti con Gramsci (1999) and Modernità alternative. Il Novecento di Antonio Gramsci (2017). He has also directed numerous recovery investigations, and first editions, of the Letters from Prison and the Prison Notebooks.

Professor of philosophy and Marxist theorist. In Italy, his work was seen by many as a 'scientific' alternative to the Gramscian Marxism which the PCI (among others) had claimed as its guide. He was also noted for his writings on aesthetics including writings on film theory. He was an atheist. Some of his most notable works include: Critique of Taste (Verso Books, 1991). Logic as a Positive Science (Verso Books, 1980). Rousseau and Marx: And Other Writings (Lawrence and Wishart, 1987). He had a number of students and disciples including Ignazio Ambrogio, Umberto Cerroni, Lucio Colletti, Nicolao Merker, Alessandro Mazzone, Armando Plebe, Mario Rossi, and Carlo Violi

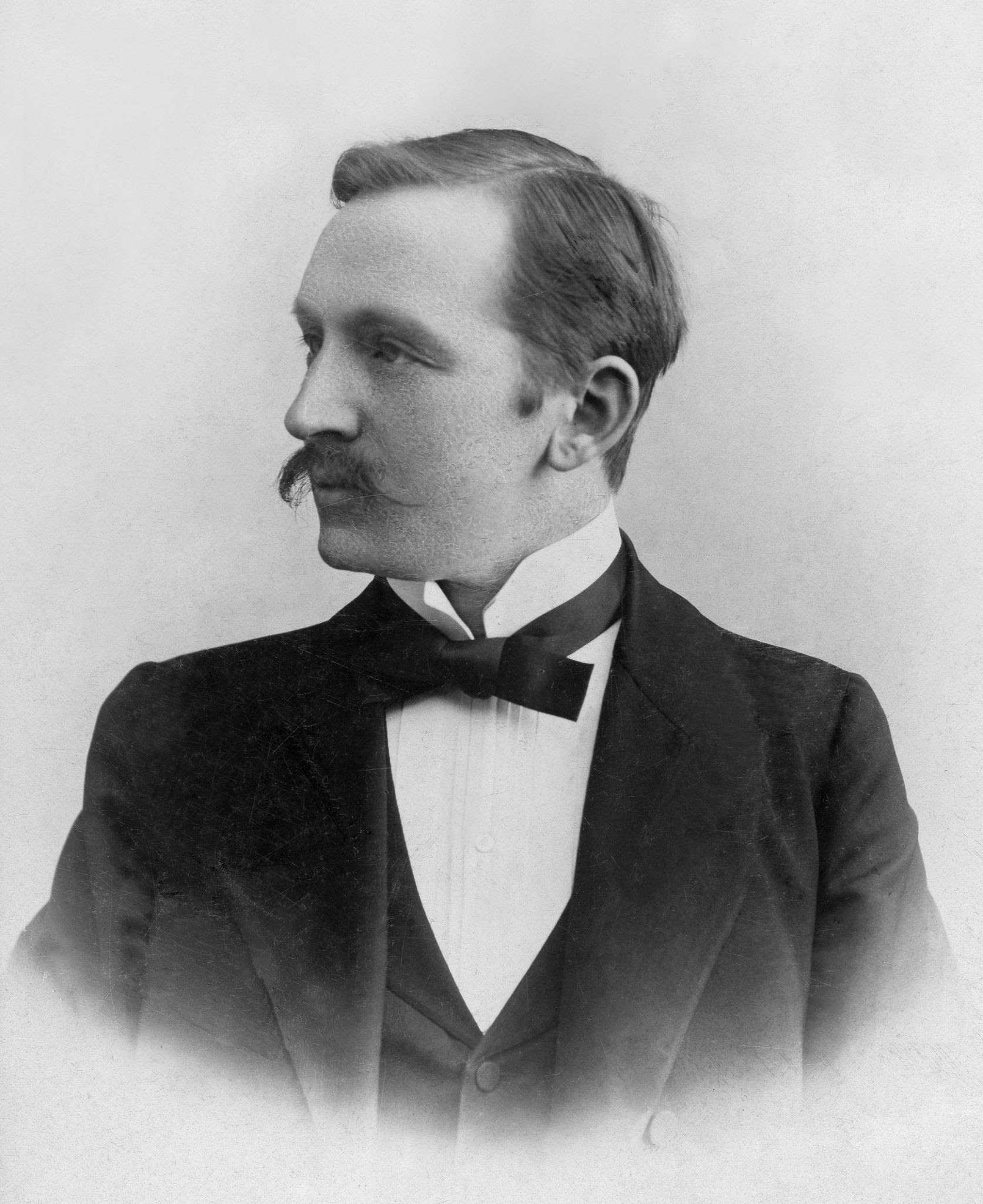

Ernest Belfort Bax (23 July 1854 – 26 November 1926) was an English socialist journalist and philosopher, associated with the Social Democratic Federation (SDF). Born into a nonconformist religious family in Leamington, he was first introduced to Marxism while studying philosophy in Germany. He combined Karl Marx's ideas with those of Immanuel Kant, Arthur Schopenhauer and Karl Robert Eduard von Hartmann. Keen to explore possible metaphysical and ethical implications of socialism, he came to describe a "religion of socialism" as a means to overcome the dichotomy between the personal and the social, and also that between the cognitive and the emotional. He saw this as a replacement for organised religion, and was a fervent atheist, keen to free workers from what he saw as the moralism of the middle-class. Bax moved to Berlin and worked as a journalist on the Evening Standard. On his return to England in 1882, he joined the SDF, but grew disillusioned and in 1885 left to form the Socialist League with William Morris. After anarchists gained control of the League, he rejoined the SDF, and became the chief theoretician, and editor of the party paper Justice. He opposed the party's participation in the Labour Representation Committee, and eventually persuaded them to leave. Almost throughout his life, he saw economic conditions as ripe for socialism, but felt this progress was delayed by a lack of education of the working class. Bax supported Karl Kautsky over Eduard Bernstein, but Kautsky had little time for what he saw as Bax's utopianism, and supported Theodore Rothstein's efforts to spread a more orthodox Marxism in the SDF. Initially very anti-nationalist, Bax came to support the British in World War I, but by this point he was concentrating on his career as a barrister and did little political work. Bax was an ardent anti feminist since, according to Bax, feminism was a part of the "anti-man crusade". According to Bax, "anti-man crusades" were responsible for "anti-man laws" during the time of men-only voting in England. Bax wrote many articles in The New Age and elsewhere about English laws partial to women against men, and women's privileged position before the law, and expressed his view that women's suffrage would unfairly tip the balance of power to women. In 1908 he wrote The Legal Subjection of Men as a response to John Stuart Mill's 1869 essay "The Subjection of Women." In 1913 he published an essay, The Fraud of Feminism, detailing feminism's adverse effects. Section titles included "The Anti-Man Crusade", "The 'Chivalry' Fake", "Always The 'Injured Innocent'", and "Some Feminist Lies and Fallacies". Bax died in London. More: http://www.marxists.org/archive/bax/ http://www.marxists.org/archive/bax/b... http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/... http://ernestbelfortbax.com/2014/01/2...

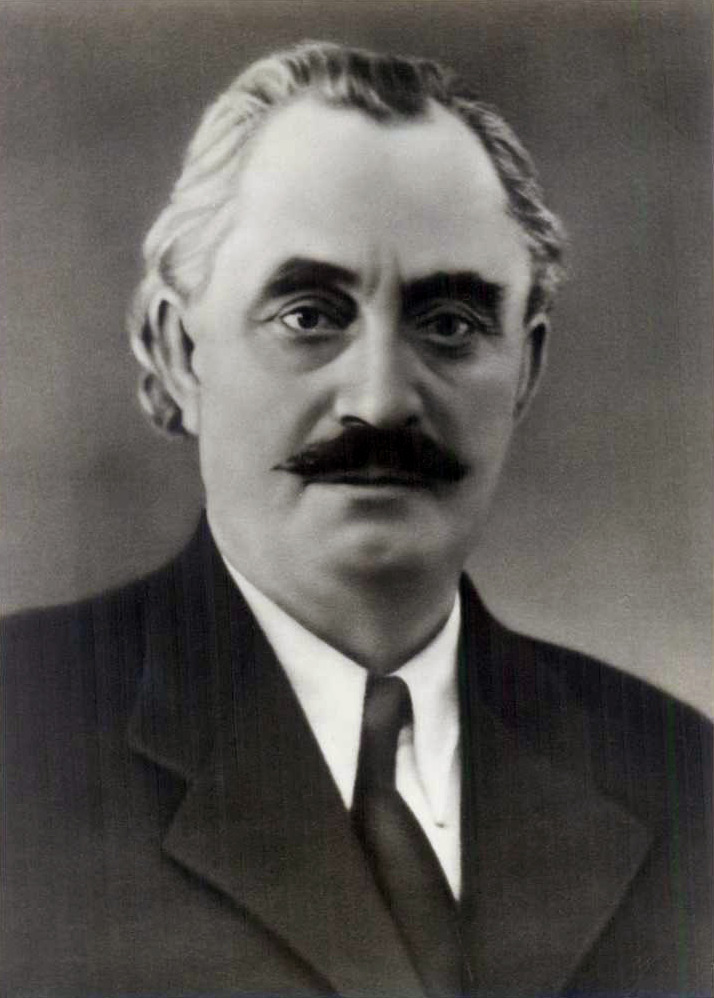

Émile Guillaume Vandervelde was a Belgian socialist politician and statesman. He graduated as a doctor in law (1885) at the ULB and settled as a lawyer in Brussels. He also graduated as a doctor in social sciences (1888) and obtained a special doctorate in state economics (1892). Nicknamed "le patron" (the boss), Vandervelde was a leading figure in the Belgian Labour Party (POB–BWP) and in international socialism.

Karol Cyryl Modzelewski was a Polish historian, writer, politician and academic. He was the adopted son of Zygmunt Modzelewski. A professor at the University of Wrocław and the University of Warsaw, he was a member of the Polish United Workers Party but was expelled from it in 1964 for opposition to some policies of the party. With Jacek Kuroń he co-wrote the Open Letter to the Party, for which he was imprisoned for three years. He took part in the Polish 1968 political crisis, and for his activities he was again imprisoned for three and a half years. During the 1980 strikes he came up with the name of 'Solidarity'. He was one of the Solidarity press contacts, and a member of the Solidarity region in Silesia. He was interned with many others during the martial law in Poland. From 1989 to 1991 he was a member of the Polish Senat (Solidarity Citizens' Committee), supporting the left-wing, particularly the Labour Union party and later Włodzimierz Cimoszewicz. Source: wikipedia

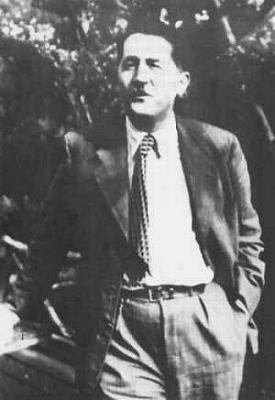

Paul Mattick, Sr. (March 13, 1904 – February 7, 1981) was a Marxist political writer and social revolutionary, whose thought can be placed within the council communist and left communist traditions. Father of author Paul Mattick Jr..

1881-1938 Austrian Social Democrat who is considered one of the leading thinkers of the left-socialist Austro-Marxist grouping. He was also an early inspiration for both the New Left movement and Eurocommunism in their attempt to find a "Third way" to democratic socialism.

Economist, close to the Democratic Party of the Left. Son of the Marxist philosopher Antonio. Rodolfo Banfi, after having participated in the resistance, had graduated in law in 1946 at University of Milan, entering the Italian Commercial Bank, where he led the research department. After a first marriage with Rossana Rossanda, he then married Francesca Trimarchi. In 1979, Rodolfo Banfi was named president of the Central Mediocredito and later became president of Sofipa, the financial participation of Mediocrediti, and Sofipa brokerage. After spending six months from the end of 1990, President of ATM, the municipal transport company in Milan, had received the purpose of monitoring, as an independent member of the Board of Trustees, the budget of the PDS Milan Federation.

Rossanda was born in Pula (Croatia), then part of Italy. She studied in Milan and was a pupil of philosopher Antonio Banfi. At a very young age, she took part in the Italian resistance and, after the end of World War II, she entered the Italian Communist Party (PCI). After a short period, secretary Palmiro Togliatti named her responsible of culture in the party. She was elected for the first time in the Italian Chamber of Deputies in 1963. In 1968 she published a small essay, entitled L'anno degli studenti ("The Year of the students"), in which she declared her support to the youth movement. Rossanda was part of a minority inside PCI that was against the Soviet Union, and, together with Luigi Pintor, Valentino Parlato and Lucio Magri founded the party and newspaper il manifesto. This caused her expulsion from the Communist Party after its XII National Congress held in Bologna. At the 1972 elections, Il Manifesto obtained only the 0,8% of the votes. It therefore merged with the Proletarian Unity Party, forming the Proletarian Unity Party for Communism. She later abandoned party politics but kept her role as director of il manifesto. Rossanda is currently is a member of the editorial board of Sin Permiso.

Historian and academic. He dealt particularly with the history of the communist movement and the problems of the world of work. After studying the Giolittian age and the origins of Italian socialism, he concentrated his interests on the period between the two wars and on Republican Italy.

Peruvian diplomat. After receiving his early education in Arequipa at the Escuela San Vicente and San José (Colegio San José), he decided to study law at the Universidad Nacional de San Agustín de Arequipa and later transferred to finish his studies at the National University of San Marcos in Lima. In addition to receiving his law degree, he also obtained doctorates in political sciences and administration and in literature in 1911. Belaúnde occupied several positions throughout his professional career. He also lectured on Hispanic-American culture throughout various universities in the United States while in exile. He died in New York City.

Jules Frederic Humbert-Droz was a Communist and a founding member of the Communist Party of Switzerland. He held high Comintern office through the 1920s and also acted as Comintern emissary to several west European countries. Prior to his becoming a Communist, Humbert-Droz was a pastor. He stayed at the Hotel Lux in Moscow. He was a member of the Executive Committee of the Communist International, but was involved in the Right Opposition in 1928 and was relocated from Moscow to Latin America. He became a Social Democrat in the 1950s.

Marxist historian, sociologist and orientalist. He was the son of a Russian-Polish clothing trader and his wife who both died in the Auschwitz concentration camp. After studying oriental languages, he became a professor of Ethiopian (Amharic) at EPHE (École Pratique des Hautes Études, France). He was the author of a rich body of work, including the book Muhammad, a biography of the prophet of Islam. Rodinson joined the French Communist Party in 1937 for "moral reasons", but later turned away after the party's Stalinist drift. He was expelled from the party in 1958. He became well known in France when he expressed sharp criticism of Israel, particularly opposing the settlement policies of the Jewish state. Some credit him with coining the term "Islamic fascism" (le fascisme islamique) in 1979, which he used to describe the Iranian revolution.

Karl Marx, Ph.D. (University of Jena, 1841) was a social scientist who was a key contributor to the development of Communist theory. Marx was born in Trier, a city then in the Kingdom of Prussia's Province of the Lower Rhine. His father, born Jewish, converted to Protestantism shortly before Karl's birth in response to a prohibition newly introduced into the Rhineland by the Prussian Kingdom on Jews practicing law. Educated at the Universities of Bonn, Jena, and Berlin, Marx founded the Socialist newspaper Vorwärts! in 1844 in Paris. After being expelled from France at the urging of the Prussian government, which "banished" Marx in absentia, Marx studied economics in Brussels. He and Engels founded the Communist League in 1847 and published the Communist Manifesto. After the failed revolution of 1848 in Germany, in which Marx participated, he eventually wound up in London. Marx worked as foreign correspondent for several U.S. publications. His Das Kapital came out in three volumes (1867, 1885 and 1894). Marx organized the International and helped found the Social Democratic Party of Germany. Although Marx was not religious, Bertrand Russell later remarked, "His belief that there is a cosmic force called Dialectical Materialism which governs human history independently of human volitions, is mere mythology" (Portraits from Memory, 1956). Marx once quipped, "All I know is that I am not a Marxist" (according to Engels in a letter to C. Schmidt; see Who's Who in Hell by Warren Allen Smith). D. 1883. Marx began co-operating with Bruno Bauer on editing Hegel's Philosophy of Religion in 1840. Marx was also engaged in writing his doctoral thesis, The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature, which he completed in 1841. It was described as "a daring and original piece of work in which Marx set out to show that theology must yield to the superior wisdom of philosophy": the essay was controversial, particularly among the conservative professors at the University of Berlin. Marx decided, instead, to submit his thesis to the more liberal University of Jena, whose faculty awarded him his PhD in April 1841. As Marx and Bauer were both atheists, in March 1841 they began plans for a journal entitled Archiv des Atheismus (Atheistic Archives), but it never came to fruition. Marx has been described as one of the most influential figures in human history. Marx is typically cited, with Émile Durkheim and Max Weber, as one of the three principal architects of modern social science. More: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karl\_Marx http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/marx/ http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/bi... http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/... http://www.historyguide.org/intellect... http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic... http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/... http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/t...

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (Russian: Иосиф Виссарионович Сталин; born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili, Georgian: იოსებ ბესარიონის ძე ჯუღაშვილი, Russian: Ио́сиф Виссарио́нович Джугашви́ли) was General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee from 1922 until his death in 1953, effectively ruling the country with dictatorial control. Stalin led the USSR through its period of industrialisation, which would become the fastest in history, surpassing Germany and Japan. On the ideological front, he developed the theory of Socialism in One Country.

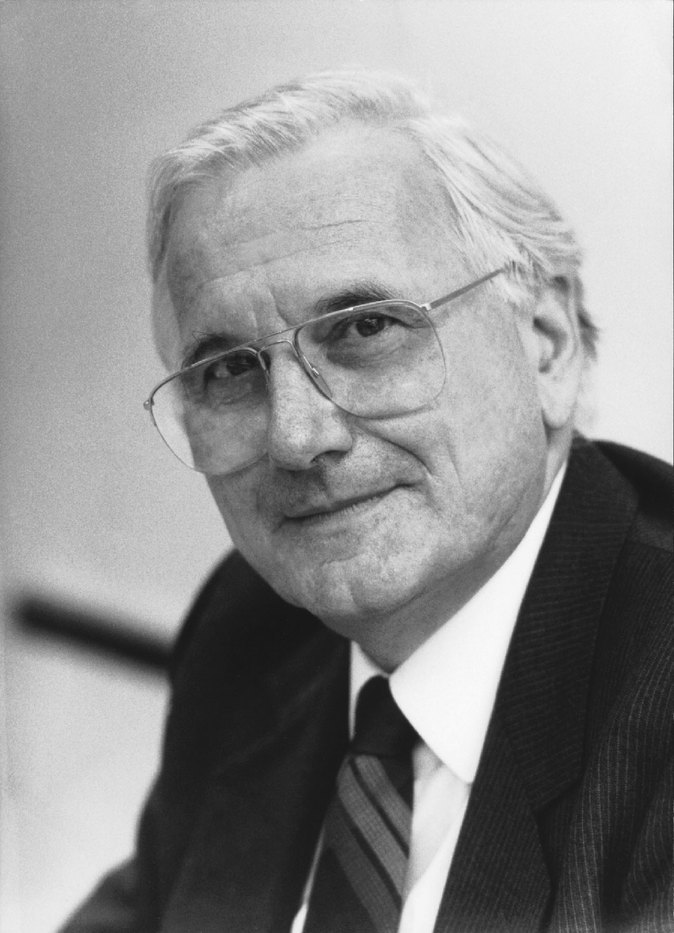

Massimo Luigi Salvadori, spesso citato come Massimo L. Salvadori (Ivrea, 1936), è uno storico e politico italiano. Professore emerito, ordinario di Storia delle Dottrine Politiche nell'Università di Torino. Membro del Comitato scientifico della Fondazione Luigi Einaudi di Torino, nel quale ha coperto per alcuni anni la carica di Presidente. Socio corrispondente dell'Accademia delle Scienze di Torino dal 1980, è dal 1997 socio nazionale residente nella classe di Scienze morali, storiche e filologiche. Collabora con il quotidiano la Repubblica.

Historian, politician and Czechoslovak resistance fighter during the German occupation of Czechoslovakia (1938–1945). Hájek, who signed the Charter 77 human rights manifesto in 1977, became the spokesman for the Charter 77 movement in 1988. In 1938, Nazi Germany began its occupation of Czechoslovakia. Together with his later wife Alena Hájková, Hájek became involved with the Czech resistance and other anti-Nazi groups to help Jews obtain hideouts and false identity papers during World War II. He was arrested by the Gestapo in August 1944 and sentenced to death in March 1945. However, his execution was not carried out before the Prague uprising and the end of the German occupation. He was later honored as "Righteous Among the Nations" by Israel for his work to save Jews during the Holocaust. Hájek became a member of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ) following the war, but opposed the KSČ's party leadership throughout the country's Communist era. He broke with the party's leaders during the Prague Spring in 1968 to join the reform movement. He was expelled from the Communist Party following the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia, which ended the Prague Spring. He was also fired from his job, but went into retirement because he had been a World War II resistance fighter. In 1977, Hájek joined with a group of Czechoslovak dissidents, including Václav Havel, to sign the Charter 77 human rights manifesto.

Lenin, Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov (1870-1924) -one of the leaders of the Bolshevik party since its formation in 1903- led the Bolsheviks to power in October, 1917. Elected to the head of the Soviet government until 1922, when he retired due to ill health. Lenin, born in 1870, was committed to revolutionary struggle from an early age - his elder brother was hanged for the attempted assassination of Czar Alexander III. In 1891 Lenin passed his Law exam with high honors, whereupon he took to representing the poorest peasantry in Samara. After moving to St. Petersburg in 1893, Lenin's experience with the oppression of the peasantry in Russia, coupled with the revolutionary teachings of G V Plekhanov, guided Lenin to meet with revolutionary groups. In April 1895, his comrades helped send Lenin abroad to get up to speed with the revolutionary movement in Europe, and in particular, to meet the Emancipation of Labour Group, of which Plekhanov head. After five months abroad, traveling from Switzerland to France to Germany, working at libraries and newspapers to make his way, Lenin returned to Russia, carrying a brief case with a false bottom, full of Marxist literature. On returning to Russia, Lenin and Martov created the League for the Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class, uniting the Marxist circles in Petrograd at the time. The group supported strikes and union activity, distributed Marxist literature, and taught in workers education groups. In St. Petersburg Lenin begins a relationship with Nadezhda Krupskaya. In the night of December 8, 1895, Lenin and the members of the party are arrested; Lenin sentenced to 15 months in prison. By 1897, when the prison sentence expired, the autocracy appended an additional three year sentence, due to Lenin's continual writing and organising while in prison. Lenin is exiled to the village of Shushenskoye, in Siberia, where he becomes a leading member of the peasant community. Krupskaya is soon also sent into exile for revolutionary activities, and together they work on party organising, the monumental work: The Development of Capitalism in Russia, and the translating of Sidney and Beatrice Webb's Industrial Democracy. After his term of exile ends, Lenin emigrates to Münich, and is soon joined by Krupskaya. Lenin creates Iskra, in efforts to bring together the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, which had been scattered after the police persecution of the first congress of the party in 1898. [...:] After leading the October Revolution, Lenin served as the first and only chairman of the R.S.F.S.R.. In 1919 Lenin founded the Communist International. In 1921 Lenin instituted the NEP. During 1922 Lenin suffered a series of strokes that prevented active work in government. While in his final year – late 1922 to 1923 – Lenin wrote his last articles where he outlined a programme to fight against the bureaucratization of the Commmunist Party and the Soviet state. Lenin died on January 21, 1924, as a result of multiple strokes.

Paul Marlor Sweezy (April 10, 1910 – February 27, 2004) was a Marxist economist, political activist, publisher, and founding editor of the long-running magazine Monthly Review. He is best remembered for his contributions to economic theory as one of the leading Marxian economists of the second half of the 20th century. Paul Sweezy was born on April 10, 1910 in New York City and attended Phillips Exeter Academy. He went on to Harvard and was editor of The Harvard Crimson, graduating magna cum laude in 1932. Having completed his undergraduate coursework, his interests shifted from journalism to economics. Sweezy spent the 1931–32 academic year taking courses at the London School of Economics, traveling to Vienna to study on breaks. It was at this time that Sweezy was first exposed to Marxian economic ideas. He made the acquaintance of Harold Laski, Joan Robinson and other young left-wing British thinkers of the day. Upon his return to the United States, Sweezy again enrolled at Harvard, from which he received his doctorate degree in 1937. During his studies, Sweezy had become the "ersatz son" ("ersatz" meaning "replacement" in German) of the renowned, Czech-born economist Joseph Schumpeter, although on an intellectual level, their views were diametrically opposed. Later, as colleagues, their debates on the "Laws of Capitalism" were of legendary status for a generation of Harvard economists. While at Harvard, Sweezy founded the academic journal The Review of Economic Studies and published essays on imperfect competition, the role of expectations in the determination of supply and demand, and the problem of economic stagnation. Sweezy became an instructor at Harvard in 1938. It was there that he helped establish a local branch of the American Federation of Teachers, the Harvard Teachers' Union. In this interval also Sweezy wrote lectures that later became one of his most important works of economics, The Theory of Capitalist Development (1942), a book which summarized the labor theory of value of Marx and his followers. The book was the first in English to deal with such questions as the transformation problem thoroughly. Sweezy worked for several New Deal agencies analyzing the concentration of economic power and the dynamics of monopoly and competition. This research included the influential study for the National Resources Committee, "Interest Groups in the American Economy" which identified the eight most powerful financial-industrial alliances in US business. From 1942 to 1945, Sweezy worked for the research and analysis division of the Office of Strategic Services. Sweezy was sent to London, where his work for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) required his monitoring British economic policy for the US government. He went on to edit the OSS's monthly publication, European Political Report. Sweezy received the bronze star for his role in the war. He was the recipient of the Social Science Research Council Demobilization Award at war's end. Sweezy wrote extensively for the liberal press during the post-war period, including such publications as The Nation and The New Republic, among others. He also wrote a book, Socialism, published in 1949, as well as a number of shorter pieces which were collected in book form as The Present as History in 1953. In 1947 Sweezy quit his teaching position at Harvard, with two years remaining on his contract, to dedicate himself to full-time writing and editing. In 1949, Sweezy and Leo Huberman founded a new magazine called Monthly Review, using money from historian and literary critic F. O. Matthiessen. The first issue appeared in May of that year, and included Albert Einstein's article "Why Socialism?". The magazine, established in the midst of the American Red Scare, describes itself as socialist "independent of any political organization". Monthly Review rapidly expanded into the production of books and pamphlets through its publishing arm, Monthly Review Press

André Gorz, pen name of Gérard Horst, born Gerhard Hirsch, also known by his pen name Michel Bosquet, was an Austrian and French social philosopher. Also a journalist, he co-founded Le Nouvel Observateur weekly in 1964. A supporter of Jean-Paul Sartre's existentialist version of Marxism after World War Two, in the aftermath of the May '68 student riots, he became more concerned with political ecology. In the 1960s and 1970s, he was a main theorist in the New Left movement. His central theme was wage labour issues such as liberation from work, just distribution of work, social alienation, and Guaranteed basic income

By Daniel Singer, published in The Independent, August 10th 1990. TAMARA DEUTSCHER, although a gifted writer and intellectual in her own right, devoted most of her active life first to collaborating closely with her husband, the well-known socialist historian Isaac Deutscher, and then to perpetuating the influence of his ideas. She was horn Tamara Lebenhaft in 1913 in Lodz, the Polish Manchester, in an intellectual family that was to be almost entirely wiped out by the Holocaust. Having gone to school in her home town and then to college in Belgium, she came to Britain in 1940 after the fall of France and lived here most of her adult life. Indeed, it was in wartime London that she took the crucial decision that was to shape that life. A beautiful young woman of great charm and a budding literary critic, Tamara was greatly admired in the highest circles of the Polish government in exile, with which she was professionally connected. But she chose as partner for life a fellow Pole who was for them an outcast, the very enemy of the establishment, the socialist and Marxist writer Isaac Deutscher, who was then at the beginning of his journalistic career. The two travelled together as war and post-war correspondents in Germany. Tamara, however, decided to interrupt her own career, convinced as she was that Isaac was destined to accomplish more lasting things. She encouraged him when he, in turn, chose to give up journalism and devote himself full-time to writing books. There followed a long period of intensive creative activity. These were also the years of the Cold War and, therefore, of awkward, painful isolation. In their ivory tower, Tamara was not only the wife and mother of their beloved Martin, she was a most efficient assistant, a thorough researcher, a devoted critic. The books, notably the three-volume biography of Trotsky (1954-63), were at the same time, as she put it, deep "links in their friendship". By the mid-sixties came the psychological reward. Deutscher's books were no longer just greeted with critical acclaim. They were a source of inspiration to an entirely new generation brought into politics by the movement against the war in Vietnam. But they were to have very little time to enjoy this new mood. In 1967 Tamara's world was shattered by Isaac's sudden death. In the many years that followed she did show, to some extent, what she had sacrificed in order to help in a major intellectual venture. Her essays and reviews revealed a lively pen, a witty mind, a critical spirit. She produced, inter alia, a Lenin anthology (Not By Politics Alone). Others, notably Professor E.H. Carr, could now get an idea what a valuable assistant and collaborator she could be. And yet, to a very large extent, she went on with her former task. Devoting her time to the Deutscher memorial prize committee, editing and prefacing his books and essays, preserving and extending the circle of younger friends, notably of the New Left Review, she had the feeling of remaining true to the cause of genuine socialism. These last months, as the countries of Eastern European were opting for capitalism and the Western world was proclaiming the end of history, the wind clearly was not blowing in her direction. She would have preferred, say, if her former compatriots had chosen other gods, or rather no god at all. But this did not shake her fundamental confidence. She had a sense of perspective and had no doubt that, sooner rather than later, the monumental Trotsky trilogy would have a seminal influence in Russia and throughout the former Soviet empire. Altogether, she was convinced that the crucial choice she had made was not only highly rewarding in personal terms, but was also historically right, whatever the current odds.

Perry Anderson is an English Marxist intellectual and historian. He is Professor of History and Sociology at UCLA and an editor of the New Left Review. He is the brother of historian Benedict Anderson. He was an influence on the New Left. He bore the brunt of the disapproval of E.P. Thompson in the latter's The Poverty of Theory, in a controversy during the late 1970s over the scientific Marxism of Louis Althusser, and the use of history and theory in the politics of the Left. In the mid-1960s, Thompson wrote an essay for the annual Socialist Register that rejected Anderson's view of aristocratic dominance of Britain's historical trajectory, as well as Anderson's seeming preference for continental European theorists over radical British traditions and empiricism. Anderson delivered two responses to Thompson's polemics, first in an essay in New Left Review (January-February 1966) called "Socialism and Pseudo-Empiricism" and then in a more conciliatory yet ambitious overview, Arguments within English Marxism (1980). http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perry\_An...

Ernesto "Che" Guevara, commonly known as El Che or simply Che, was a Marxist revolutionary, physician, author, intellectual, guerrilla leader, diplomat, and military theorist. A major figure of the Cuban Revolution, since his death Guevara's stylized visage has become an ubiquitous countercultural symbol and global icon within popular culture. His belief in the necessity of world revolution to advance the interests of the poor prompted his involvement in Guatemala's social reforms under President Jacobo Arbenz, whose eventual CIA-assisted overthrow solidified Guevara's radical ideology. Later, while living in Mexico City, he met Raúl and Fidel Castro, joined their movement, and travelled to Cuba with the intention of overthrowing the U.S.-backed Batista regime. Guevara soon rose to prominence among the insurgents, was promoted to second-in-command, and played a pivotal role in the successful two year guerrilla campaign that topled the Cuban government. After serving in a number of key roles in the new government, Guevara left Cuba in 1965 to foment revolution abroad, first unsuccessfully in Congo-Kinshasa and later in Bolivia, where he was captured by CIA-assisted Bolivian forces and executed. Guevara remains both a revered and reviled historical figure, polarized in the collective imagination in a multitude of biographies, memoirs, essays, documentaries, songs, and films. Time magazine named him one of the 100 most influential people of the 20th century, while an Alberto Korda photograph of him entitled "Guerrillero Heroico," was declared "the most famous photograph in the world" by the Maryland Institute of Art.

J. P. Nettl (1926–1968) was a historian best known for his two-volume biography of Rosa Luxemburg, which The New York Times described as a classic work that did full justice to her political activity, context, theoretical contributions, and personality. He lived in England from 1936. After serving with British army intelligence during the Second World War, he studied at Oxford. He died in a plane crash in the United States in 1968.

Claude Lévi-Strauss was a French anthropologist, well-known for his development of structural anthropology. He was born in Belgium to French parents who were living in Brussels at the time, but he grew up in Paris. His father was an artist, and a member of an intellectual French Jewish family. Lévi-Strauss studied at the University of Paris. From 1935-9 he was Professor at the University of Sao Paulo making several expeditions to central Brazil. Between 1942-1945 he was Professor at the New School for Social Research. In 1950 he became Director of Studies at the Ecole Practique des Hautes Etudes. In 1959 Lévi-Strauss assumed the Chair of Social Anthroplogy at the College de France. His books include The Raw and the Cooked, The Savage Mind, Structural Anthropology and Totemism (Encyclopedia of World Biography). Some of the reasons for his popularity are in his rejection of history and humanism, in his refusal to see Western civilization as privileged and unique, in his emphasis on form over content and in his insistence that the savage mind is equal to the civilized mind. Lévi-Strauss did many things in his life including studying Law and Philosophy. He also did considerable reading among literary masterpieces, and was deeply immersed in classical and contemporary music. Lévi-Strauss was awarded the Wenner-Gren Foundation's Viking Fund Medal for 1966 and the Erasmus Prize in 1975. He was also awarded four honorary degrees from Oxford, Yale, Havard and Columbia. Strauss held several memberships in institutions including the National Academy of Sciences, the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the American Philosophical Society (Encyclopedia of World Biography).

Professor of sociology of work at the University of Milano. She has been working on social theory, trade unions, social movements and gender; lately, she has been involved in current European debates on political representation and quotas. She has been on the national board of the Italian Equal Opportunities Commission; she is now the director of the Center for Women's Studies and Gender Studies of the University of Milano.

German historian. She came from a family of upper middle class, mostly spent her childhood in Vienna and Sofia and engaged already in their youth in the socialist labor movement. She did not returned from a stay in the UK, after the annexation of Austria to Nazi Germany because of her political beliefs and their Jewish origin. Instead, she became involved in London in exile circles, which also belonged to her later partner and husband Willi Eichler. After the end of World War II, she went with him to Cologne and then to Bonn to take part in Germany's political reconstruction. Miller worked in the 1950s as an employee of the national leadership of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and worked among other things, in the creation of the Godesberg program. From 1960 to 1963 she continued her studies in Bonn, which she had broken off in the 1930s, and graduated with a program-historical work of German social democracy. Then she was an employee of the Commission for the History of parliamentarism and the political parties. Her historiographical works deal mainly with issues of the labor movement, exile and of recent German history. Susanne Miller preferred political-historical approaches to the study of programs, ideologies and political movements.

(Greek: Αργύρης Εμμανουήλ) was a Greek-French Marxian economist who became known in the 1960s and 1970s for his theory of 'unequal exchange'. The theory was an attempt to explain the falling trend in the terms of trade for underdeveloped countries, while criticising the different approaches of Raúl Prebisch, Hans Singer, and Arthur Lewis to do so as only half-hearted attempts. It stated, contrary to the then conventional Heckscher-Ohlin-Samuelson theory, that it was politically and historically set wage-levels that determined relative prices, not the other way around, and, contrary to the assumptions of Ricardo's comparative costs, that capital was internationally mobile and the rate of profit correspondingly equalised. What made the theory a heated subject in Marxist and dependendista circles was the theory's implications about international worker solidarity. Emmanuel was not late to point out that his theory fitted well with the observed absence of such solidarity, particularly between high- and low-wage countries, and, in fact, made the nationally enclosed workers movements into the principal cause of unequal exchange. By contrast, all subsequent versions of the theory such as those by Samir Amin, Oscar Braun, Jan Otto Andersson, Paul Antoine Delarue, and almost every critic since Charles Bettelheim, have preferred to make higher productivity the cause (and thereby justification) of higher wages, and 'monopolies' the cause of unequal exchange. Emmanuel's theory of unequal exchange was part of a more comprehensive explanation of the post-war capitalist economy. In Emmanuel's view, because selling had to take place without the income generated by the sale itself, there was a permanent excess of (the value of) goods over (the purchasing power of) income in the normal workings of a market economy. This obliged the economy to function below its full potential and made it prone to crises such as the one he had himself experienced during the Great Depression. By contrast, the boom of the 'thirty glorious' post-war years indicated that this normal functioning had somehow been evaded, and Emmanuel now offered the institutionalised rise in wages, plus a policy of permanent inflation, as the principal stimulant directing the boom in investments. Since neither the wage- nor the consumption levels of the well-off countries could be internationally equalised - upwards for both ecological reasons and because it would eat up all profits, and downwards for political reasons in the same rich countries - unequal exchange was the necessary consequence, in a sense saving the capitalist economy from itself.

Sergio Bologna lives in Italy and is known for his active participation since the 1960s in the workers' current and later, during the 1970s, in workers' autonomy. Sergio Bologna was a founding member of the organization "Workers Power" [Potere Operaio] and together with Antonio Negri and Franco Piperno formed the first general secretariat of the organization in 1969. He left the organization in 1970. In 1960 and 1970 he participated in several magazines ( Quaderni Rossi, Cronache Operaia, Quaderni Piacentini, Linea di Massa) where he contributed fruitful analyzes of capitalist development, new labor figures, the form of the state after World War II, cycles of struggle in Italy and the meaning of labor autonomy. One such analysis, and perhaps the best known in our parts, is "The Race of Moles", published in the spring of 1977 in the historical review Primo Maggio, which he founded in 1973. He has taught at the University of Trento and as a professor of Labor Movement History at the University of Padua. Recently he deals with the changes marked by the development of the tertiary sector, the new figures of intellectual workers, precarious workers and the problems of their collective organization. He also writes for the newspaper "Manifesto".

Dutch astronomer and marxist theorist. He was one of the main theorists of council communism. As a recognized Marxist theorist, Pannekoek was one of the founders of the council communist tendency and a main figure in the radical left in the Netherlands and Germany. In his scientific work, Pannekoek started studying the distribution of stars through the Milky Way, as well as the structure of our galaxy. Later he became interested in the nature and evolution of stars. Because of these studies, he is considered to be the founder of astrophysics as a separate discipline in the Netherlands. The Astronomical Institute Anton Pannekoek at the University of Amsterdam, of which he had been a director, still carries his name.

György Lukács was a Hungarian Marxist philosopher, aesthetician, literary historian and critic. He is a founder of the tradition of Western Marxism, an interpretive tradition that departed from the Marxist ideological orthodoxy of the Soviet Union. He developed the theory of reification, and contributed to Marxist theory with developments of Karl Marx's theory of class consciousness. He was also a philosopher of Leninism. He ideologically developed and organised Lenin's pragmatic revolutionary practices into the formal philosophy of vanguard-party revolution. His literary criticism was influential in thinking about realism and about the novel as a literary genre. He served briefly as Hungary's Minister of Culture as part of the government of the short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic.

Philosopher. He taught theoretical philosophy at the University of Milan from 1970 to 1999. Later, he went to live at Pietrabianca di Sangineto (Calabria), from which he continues to write and publish. He was a disciple of Enzo Paci and wrote his dissertation on Husserl's unpublished works. His philosophical position is characterised by the concept of phenomenology ("phenomenological structuralism") influenced by Husserl, Wittgenstein, and Bachelard. Some indications about phenomenological structuralism are contained in the online article: "Die Idee eines phänomenologischen Strukturalismus". His thought is oriented towards the philosophy of knowledge, the philosophy of music, and the fields of perception and imagination.

Monty Johnstone, who has died from complications following treatment for a burst ulcer, aged 78, was an admired, but for the most part lonely, presence in communist and socialist politics for half a century. He was indeed hard to overlook. The journalist Francis Beckett recalled him at the final congress of the Communist party in 1991 as "a tall, thin, imposing figure who ran his fingers through his long dark hair as he spoke and sounded like an eccentric history professor". More likely he will be remembered, looking genial and perennially youthful, cycling through London - his grandfather Sir John Foster Fraser had in 1896-97 been the first man to cycle round the world - on his way from one meeting to another to debate Marxist theory and developments in the Soviet Union and eastern Europe. Learned, a formidably multilingual traveller, as vocal about public matters as he was silent about private ones, and utterly indifferent to the comforts and conveniences of life, he seemed a modern secular version of a medieval scholarly friar. Born to CJS Montague Johnstone of the Royal Scots Greys and Margaret Fraser in Sir Walter Scott's house, Abbotsford, in Melrose, Monty joined the Young Communist League aged 12 in the unlikely milieu of Henley on Thames before going to Rugby school. After national service in Germany and communist agitation in the Hamburg dialect, he went up to Christ Church, Oxford, with a languages scholarship to study politics, philosophy and economics. After he graduated in 1952, he took a party job as editor of the Young Communist Challenge until his heterodoxy ended his party career in 1956. Perhaps he might have been happier as an academic. Monty was to remain a loyal but critical communist all his life, hostile to the dilution of socialist ideals but equally critical of the destruction of democracy in post-1917 Russia and the blind loyalty of communist parties to Moscow. Though he stayed in the party after 1956, he was viewed with suspicion, and the party press was closed to him until after the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, during which, in Prague, he tried to dissuade embarrassed Russian tank crews in fluent Russian. Meanwhile in the CP, his anti-Stalinism pioneered what later became known as Eurocommunism. He also established a reputation among the 1960s New Left, and became associated with Ralph Miliband (obituary, May 23 1994) and Isaac Deutscher. By the 1980s, the ideological shift in the CP leadership brought Monty rehabilitation within what was by then a doomed party. He was finally put on the editorial board of the Collected Works of Marx and Engels and was even elected to the CP executive committee. However, he was unsympathetic towards the wholesale revisionism of Marxism Today. None the less, in 1980 - nobody quite knows how - he secured that newspaper the journalistic coup of a double interview in Poland with the leader of Solidarity, Lech Walesa, and prime minister Mieczyslaw Rakowski. He was pessimistic about Mikhail Gorbachev's reforms, opposed the dissolution of the Communist party of Great Britain, but kept a political home in the Socialist History Society, the Alliance for Green Socialism and various continental groups analysing the failures and might-have-beens of communism. In the late 1960s, Monty gave up a successful career teaching at Woolwich Polytechnic - now part of Greenwich University - for a freelance life of writing, lecturing in Britain and abroad (he was a powerful speaker), and bringing up his children. He had a contract for a major book on the development of Leninism, but never completed that or any other book, although he published numerous lucid and persuasive lectures. Following the break-up of his marriage in the early 1970s, he became in effect a single parent. After his children grew up and left, he sold the family house and lived increasingly in unadvertised and uncomplaining poverty in a south London flat without a telephone, analysing

Argentine/ Italian historian. ICREA Research Professor at UPF (Universitat Pompeu Fabra). Humanities Professor at the UAM Iztapalapa, Mexico (1981-1986), and at the UNICEN, Tandil, Argentina (1986-1991). From 1991 he is directeur d’études at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales in Paris and from 2008, he’s ICREA Research Professor at the Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona. Director of the project State Building Process in Latin America, Advanced Grant of the European Research Council under the FPT/7 2007-2013.

E. H. Carr was a liberal realist and later left-wing British historian, journalist and international relations theorist, and an opponent of empiricism within historiography. Carr was best known for his 14-volume history of the Soviet Union, in which he provided an account of Soviet history from 1917 to 1929, for his writings on international relations, and for his book What Is History?, in which he laid out historiographical principles rejecting traditional historical methods and practices. Educated at Cambridge, Carr began his career as a diplomat in 1916. Becoming increasingly preoccupied with the study of international relations and of the Soviet Union, he resigned from the Foreign Office in 1936 to begin an academic career. From 1941 to 1946, Carr worked as an assistant editor at The Times, where he was noted for his leaders (editorials) urging a socialist system and an Anglo-Soviet alliance as the basis of a post-war order. Afterwards, Carr worked on a massive 14-volume work on Soviet history entitled A History of Soviet Russia, a project that he was still engaged in at the time of his death in 1982. In 1961, he delivered the G. M. Trevelyan lectures at the University of Cambridge that became the basis of his book, What is History?. Moving increasingly towards the left throughout his career, Carr saw his role as the theorist who would work out the basis of a new international order.

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre, normally known simply as Jean-Paul Sartre, was a French existentialist philosopher and pioneer, dramatist and screenwriter, novelist and critic. He was a leading figure in 20th century French philosophy. He declined the award of the 1964 Nobel Prize in Literature "for his work which, rich in ideas and filled with the spirit of freedom and the quest for truth, has exerted a far-reaching influence on our age." In the years around the time of his death, however, existentialism declined in French philosophy and was overtaken by structuralism, represented by Levi-Strauss and, one of Sartre's detractors, Michel Foucault.